Almost Like the Blues

Moral outrage often fails to track moral catastrophe

This post is a part of the International Shrimpact Day fundraiser — donate here to help save many millions of shrimp from painful deaths! — but also has some cool and extremely well-written stuff to say about continental philosophy discourse, effective altruism in general, and Leonard Cohen. Something for everyone!

1. Emotion Is Often Precedent to Action

Suffering is very bad. We all understand this to be true. And it seems like the thing we call “ethics” — or at least a big part of that thing — has a lot to do with reducing the amount of suffering going on in the world.

Most of the time, when we do anti-suffering acts, we’re acting emotionally. We can feel moral outrage only when the emotional substrate is already present — we need plain outrage first. To see a child drowning in a pond and calling out for help is intense and sad and extremely motivating.

To a first approximation, this is great! How convenient that we have strong emotional responses to others’ suffering, and how nice that this emotional response compels us to make things better.

But there are two problems with this picture: first, our emotions are triggered only by the most visible and obvious kinds of suffering — which, naturally, constitute a tiny minority of all the painful things happening in the world. And second, moral outrage has got a hair trigger — the same emotional response can be set off by any number of trivial stimuli.

If we want to do ethics well, we need to understand these two phenomena — our limited scope and our susceptibility to error — and find some way to work around them.

Already convinced?

Weird, I haven’t even made any arguments yet! But if you’d like to help lots of shrimps avoid extremely painful deaths, you can do so here. Just $10/month — the price of two-ish Starbucks Pumpkin Frappacrappalattos — will save 180,000 shrimps per year from horrible painful deaths.

2. Artists Are the Worst

There is a class of individuals who are paid and respected and lauded for taking our emotions — those mental states carefully crafted by evolution to arise in response to actual real things in the world and to direct our reactions in the appropriate ways — and manipulating them according to fake not-real things. These are called “artists”; their grisly trade is “art.”

Take, for instance, the “scared” response, which was designed to save us from saber-tooth tigers — and is instead used by the artist to facilitate teenage copulation by means of terrified cuddling at the drive-in horror theater. (Fine, so it’s not all bad.)

Different kinds of art are optimized to hack different emotional responses. The genre which pushes our anti-suffering buttons — that which makes us sad — we call “the blues.”

Now, already I’ve expanded this term, “the blues,” from what it really means — a kind of jazz-ish music — to the entire field of sad art, so I hope you’ll permit me to go a little further: “the blues,” for our purposes, will refer to all of the emergent social programming which tells us what ought be labeled “sad.”

We learn from blues music that loneliness and rejection are a kind of sad, just as we learn from the law that a mother letting her fourteen-year-old son behind the wheel is another.

This kind of thing really is socially-determined, at least a little — and I think it’s what non-useless continental philosophers like Foucault are trying to get at.

No, it’s not really the case that the capital-B Bad or the capital-T Truth depends on which country you live in — just that, for instance, in the US we look down on things like wifebeating and female genital mutilation, whereas in Somalia, these are considered awesome, and what’s actually sad is when a woman shows her hair in public.

This kind of bluesy social programming can be pretty powerful. Sometimes even more powerful than our more basic emotional instincts to abhor and alleviate suffering! In countries like Somalia, it’s obvious to us when this is happening, but it also goes on in the West, inside our own moral minds.

This is the point made by Leonard Cohen’s “Almost Like the Blues.” He sings:

I saw some people starving

There was murder, there was rape

Their villages were burning

They were trying to escapeI couldn’t meet their glances

I was staring at my shoes

It was acid, it was tragic

It was almost like the blues

It was almost like the blues

The picture here is of some brutal faraway war. The images are playing on TV — they’re not immediate or personal, it’s not our villages burning, but theirs. Cohen tries to personalize the conflict — imagines himself there, makes some effort to stimulate his anti-suffering instincts — but he can’t “meet their glances.” He knows, from a God’s-eye analytical view, that what’s going on is terrible and “tragic,” but can’t quite feel it. It’s only almost like the blues — the ambient culture has conditioned him against strong emotional reaction to the profound evil unfolding.

What does that ambient culture call “evil” in place of faraway suffering? For Cohen, maybe it’s got something to do with failure:

There’s torture, and there’s killing

And there’s all my bad reviews

The war, the children missing, Lord

It’s almost like the blues

It’s almost like the blues

“Bad reviews” are as deeply felt as torture and killing. Probably this is a kind of anti-capitalist or anti-meritocratic critique, which is a little frivolous — “it feels bad to fail” doesn’t do quite enough work to advocate a revolutionizing of society1 — but also is true. I find myself worrying about the quality of the work I do and the career success I will or won’t have way more than I worry about all the torture and the killing and the children missing in the world.

But surely our moral outrage can be well-directed sometimes! What about the Holocaust? everyone agrees that was pretty reprehensible right? Surely it was an appropriately animating moral catastrophe? Cohen says, not quite:

I listened to their story

Of the gypsies and the Jews

It was good, it wasn’t boring

It was almost like the blues

It was almost like the blues

The case is compelling — good, not boring — but ultimately, per Cohen, fails. Even the Holocaust couldn’t quite yank our emotions out of their immediate and narrow-minded malaise.

I think, historically, this point is basically true: we didn’t fight World War II over the Holocaust, after all! In fairness, the Holocaust didn’t get going for a little while, and it took even longer for anyone to realize it was going on.

But even once some Americans did know, they either covered it up or had a real hard time selling the truth to decision-makers. And even once the decision-makers definitely knew what was going on, they wouldn’t bomb the camps! The dominant narrative of the war simply couldn’t accommodate the terrible suffering going on in the Holocaust. It was anti-Germany (and even more anti-Japan in the US), and so emotions — meaning motivations, meaning actions — mapped that way instead.

Convinced just by that?

Wow, maybe I should look into being some kind of a professional music-analyzer-fellow. Anyway, if you’d like to help lots of shrimps avoid extremely painful deaths, you can still do so here. Just $10/month — one-third the price of a large Napoletana at Brick Oven Pizza in New Haven, CT — will save 180,000 shrimps per year from horrible painful deaths.

3. What Is to Be Done?

We have two options.

One, is to try to change the social narrative — redefine “the blues” to better reflect fundamental moral truth. This is the project of social justice, and it’s not a bad idea, but it is extremely difficult to pull off:2 shifting the social consciousness intentionally is hard, and especially so nowadays.

It has been done before: after World War II, the moral posture of the West became defined by anti-Holocaustism, by doing the opposite of whatever a Nazi would do.

But now the social consciousness is largely determined by big inscrutable algorithms. You might be able to succeed at making the war in Gaza morally outrageous to most people — but the kind of moral outrage you produce will end up extreme, stupid, and wrong.3

Alternatively, you can make an individual effort to care less about what’s blue, and more about the cold, hard, unemotional reality of vast suffering. And then you can go about finding concrete ways to alleviate that suffering.4

I think this latter approach — even though it stands in opposition to neurobiological instinct — tends to be much more productive. After all, though Society Is Fixed, Biology Is Mutable. (In this case, perhaps we should say “moral psychology is mutable.”)

Why think this can work? Because it is, in a way, the fundamental ethos of effective altruism.5 Instead of mucking about with obstinate and arbitrary socioemotional priorities, we just look for suffering — the kinds which are the worst and the hardest to see and especially the hardest to feel — and then find the best ways to reduce that suffering.

And effective altruism really really works! It has an incredible record: 200,000 lives saved, 400 million chickens uncaged, all the AI safety research ever, and YIMBYism. (That’s all as of November 2023.)

Even if you don’t want to be an Effective Altruist proper, I hope you can at least appreciate the power of this mindset. Many critics of EA will say it’s kind of gross to treat charity so analytically and so distantly — and then turn around and fail to meet the glances of anyone suffering anywhere.

This is why: because they’re still hung up on the blues — either on acting in accordance with them, or on shoving them in some new direction. And so they have an aversion to any good which can only be accessed by blues-ignorant analysis.

Now, surely, you’ve been convinced?

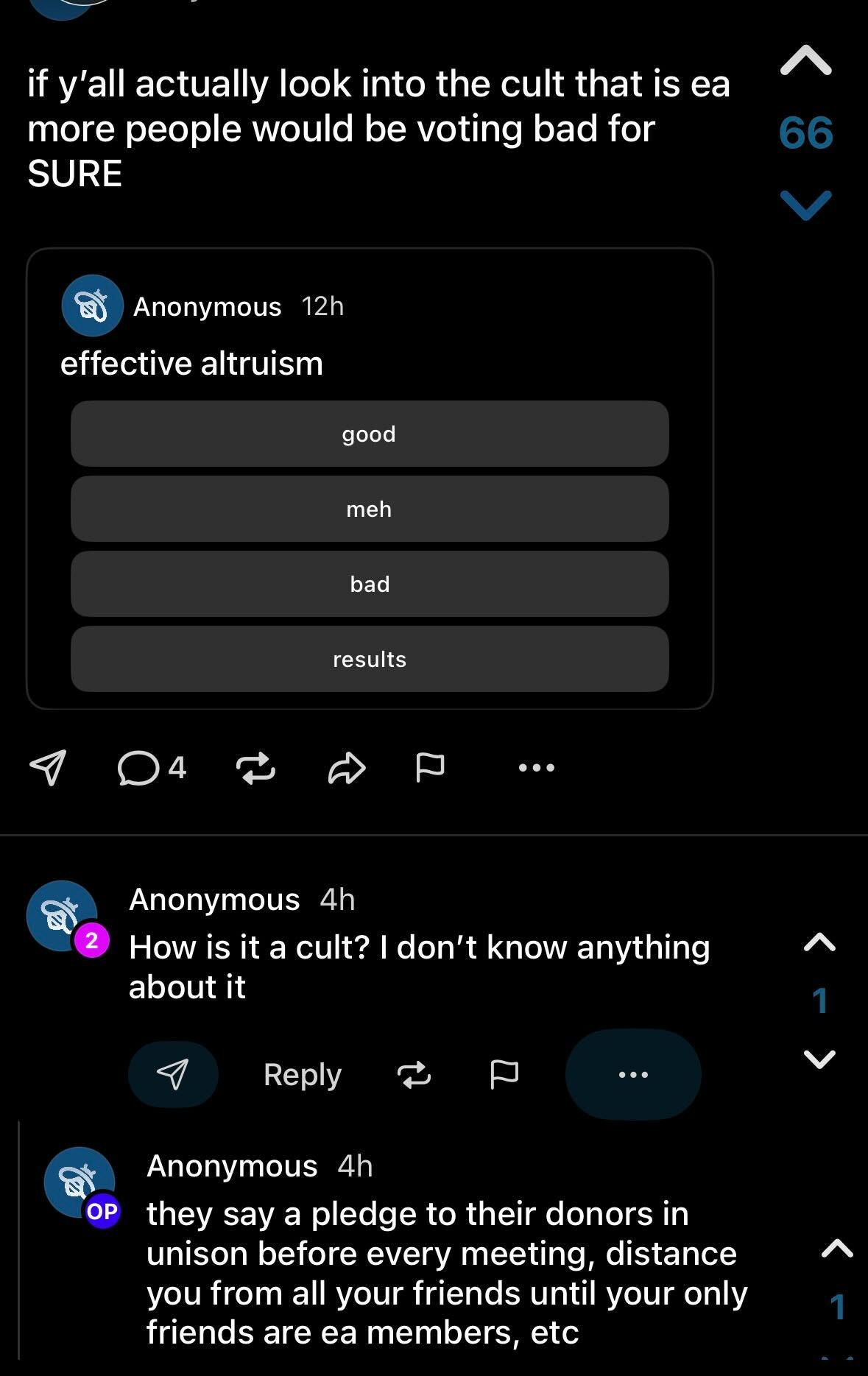

I assume this is because I’ve persuaded you to join The Cult That Is EA, and you’ve pledged fealty to whatever’s the faddiest cause area on Substack.

Welcome, comrade — follow this link, say three “Hail Dustins,” break up with your non-EA life partner, and donate just $10/month — that’s exactly the cost of one ceremonial EA “Moon Goddess” bathrobe — to save 180,000 shrimps per year from horrible painful deaths.

4. Seeing Like An EA

If you’re interested in trying the EA mindset on for size, consider with me the horrific reality of shrimp farming.

Around 440 billion shrimps are raised and slaughtered every year in utterly appalling conditions. Many undergo eyestalk ablation — farmers will yank out or burn off or crush their eyestalks in order to stimulate reproduction. And the vast majority are killed slowly: made to suffocate and freeze to death simultaneously for a period of around 20 minutes.

The science on shrimp sentience is inconclusive, but strongly suggests that they can, in fact, feel pain. This means that shrimp farming might just be the largest source of suffering in today’s world.6

Granted, no part of this is especially heartrending.

But if we find it hard to feel worse about the war in Sudan than about getting fired, I’m not sure we have any hope of an appropriate emotional response to shrimp suffering! It’s kind of like the blues — eyes are getting ripped off heads and trillions of little pain receptors are registering lethal agony — but I doubt any of this has tempted you to break down crying.

So: set the emotions aside!

The Sudanese war is worse than losing your job, and the yearly torture of hundreds of billions of shrimp is really bad too! It’s hard to make a dent in the former, but we do know how to save a lot of shrimp for very little expense. There’s a charity called the Shrimp Welfare Project, and every dollar they get is used to prevent the painful deaths of around 1,400 shrimps per year.7

SWP is big and established — they already help around 4.5 billion shrimps each year. That’s an incredible number, but it’s also only 1% of the total farmed shrimp population.

So if you find yourself with any desire to increase that share — despite the probable lack of moral outrage in your heart — you can donate here by Tuesday, December 2nd, and be matched at 50% — you’ll save 2,100 shrimp per year per dollar.

Even better: you can help me win a contest!

If you follow this donation link, or enter the matching code “shrimpweremade” on the International Shrimpact Day landing page, your donation will add to my score on the leaderboard. How neat is that!

Finally, if somehow you remain unconvinced, consider the following:

I saw some people farming

There were shrimps along the cape

Their bodies were all freezing

They were trying to escapeI couldn’t see their eyestalks

They’d been burned down like a fuse

It was acid, it was tragic

It was almost like the blues

It was almost like the bluesI have to post a little

Between each murderous crop

And when I’m finished eating

I have to post a lotThere’s torture, and there’s killing

And now my Substack’s losing views

The gore, their bodies floating, Lord

It’s almost like the blues

It’s almost like the bluesStill I let the shrimp get frozen

And keep away the thoughts

Stone, Lyman, buys a dozen

Jeff Sebo’d rather notI listened to them argue

I saw ol’ Lyman lose

It was good, it wasn’t boring

It was almost like the blues

It was almost like the bluesThey feel no pain, I know it

There is no shrimpy joy

So says the great researcher

Of baby girls and boysBut I’ve read the LSE report

I know they’ve been abused

It’s almost like salvation

It’s almost like the blues

It’s almost like the bluesAlmost like the blues

Almost like the blues

Almost like the blues

To be clear, I don’t mean to suggest that Leonard Cohen was for the revolutionizing of society! Actually, I think he was one of the rare artists capable of making a critique like this without getting way too wrapped up in it.

This was Foucault’s whole point, by the way.

Cf. The Toxoplasma of Rage for an account of why this sort of failure happens so often now. Probably there’s some way to overcome this and do successful social change again; if you know that way, please get in touch, I have some social change ideas I want to try out.

Actually, there’s not really anything about these two options which makes them mutually exclusive. So if you plan on going out and poasting about some cause — like I’m doing now — consider also finding and donating to some charity which is actually concretely making things better.

Or at least of some effective altruists. I think we probably come in two kinds: unfeeling pieces of shit who do morality in this over-analytical, color-by-numbers kind of way (e.g., me); and hyper-empathic freaks who’ve really internalized the idea that a million is made out of a million ones (e.g., Scott Alexander, maybe? I’m not 100% sure that this kind of EA definitely does exist).

Note: a decent argument can be made that insect suffering is worse. But we don’t have any great insect charity to send our cash! (There are other good things you can do for insects, though.)

They do this mostly by giving electrical stunners to farmers and corporations — the shrimps still die, but they’re knocked unconscious painlessly before slaughter. This is a lot better than the slow-torture of freezing and asphyxiating which is present common practice!

Shrimpmas has been such a whirlwind I’m only just getting a chance to read this properly. It’s great!!! Well done

I’ve heard of the Tribe in India, in which each person lives till 120 at least, no cancer what so ever: they eat only raw fruits and vegetables, and dried ones in Spring. Maybe thats the way to go not to harm shrimps, cows, poultry, and not to cause sufferings at all? Just a thought. :)