Contra Huemer on Free Will

Michael Huemer is a wonderful philosopher, and I’m about two interesting articles away from subscribing to his Fake Noûs. He’s insightful, measured, as humble as you can expect a philosopher to be, incredibly readable, and often very right.

Unfortunately, in a post from about a year and a half ago titled “A Proof of Free Will,” he’s approximately none of those things. This is my critique of his argument.

You may want to reference what I’ve written in defense of determinism and how I’ve waded confusedly through its implications. Also relevant are my thoughts on the integrity of identity (or lack thereof).

Before I get into Huemer’s argument, I have two barely-related complaints to lodge:

Bentham's Bulldog is doing something really annoying. (He’s a great writer, you should read him, he’s deeply confused about theism, etc.) My Substack Notes feed (I’m trying to quit, very unsuccessfully) is full of year-old articles that he keeps promoting. Honestly, I’m not sure if he’s doing this intentionally, but it’s overloading me with old interesting things to read and I’m falling behind on new interesting things. He’s responsible for this. Otherwise I’d be writing about a Jewy topic, but instead you get a hopelessly dense philosophy post from an untrained fool trying to bootstrap formal logic.

Philosophers have a habit of saying, “all these other philosophers who think [Important Question I’ve Thought A Lot About And Written Lots Of Papers On] has a simple resolution are so arrogant, they have no respect for why it should be a complex open question,” then turning around and writing a piece called “The Obvious Solution to [Important Question I Haven’t Thought Much About] That I Came Up With When I Was a Sophomore in College.” This is fine, and I’m saying it’s fine because I do it too (except I only do the second part, lacking any of the necessary qualifications for the first), but also it’s really annoying and everyone else should stop doing it.

This is the post in question; I’ll summarize what’s important, but you can go read it if you don’t trust me:

Michael Huemer got interested in Free Will vs. Determinism as a college student, thought of an argument for free will, and wrote it up as a term paper. He says he tried to publish it as a professor, but repeatedly failed when “referees said to reject it because they could think of some objections to my argument.”

He says this was unfair, blah blah blah, his argument is super cool and edgy and no one likes it, more blah blah blah, eventually he got (some) of it published in a book chapter.1

He explains that his proof is derived from an intuition to doubt determinism: Basically, a determinist’s argument isn’t actually convincing because a determinist can’t make any argument about anything! To a determinist, it all just is as it is, so if a determinist says, “I believe in determinism,” it’s not because he has good reason to, it’s just what he’s been conditioned to say. A determinist can’t really argue against someone who believes in free will because, similarly, that belief is totally naturally conditioned, and it’d be futile to oppose God’s the universe’s will.

“In its most common (physicalistic) forms, per Lucas, determinism implies that good reasons play no role in explaining why one believes determinism itself. So the determinist couldn’t hold that he himself knows determinism to be true.”

This is cute, but fundamentally confused. And the confusion comes from, frankly, a bit of question begging. The argument purports to say, “the determinist has no epistemic ground if determinism is true,” but really it’s saying “the determinist has no epistemic ground if determinism has been true exactly up to this point in time and then suddenly we just switched over to free will.” Essentially, it’s a strange, circular strawman.

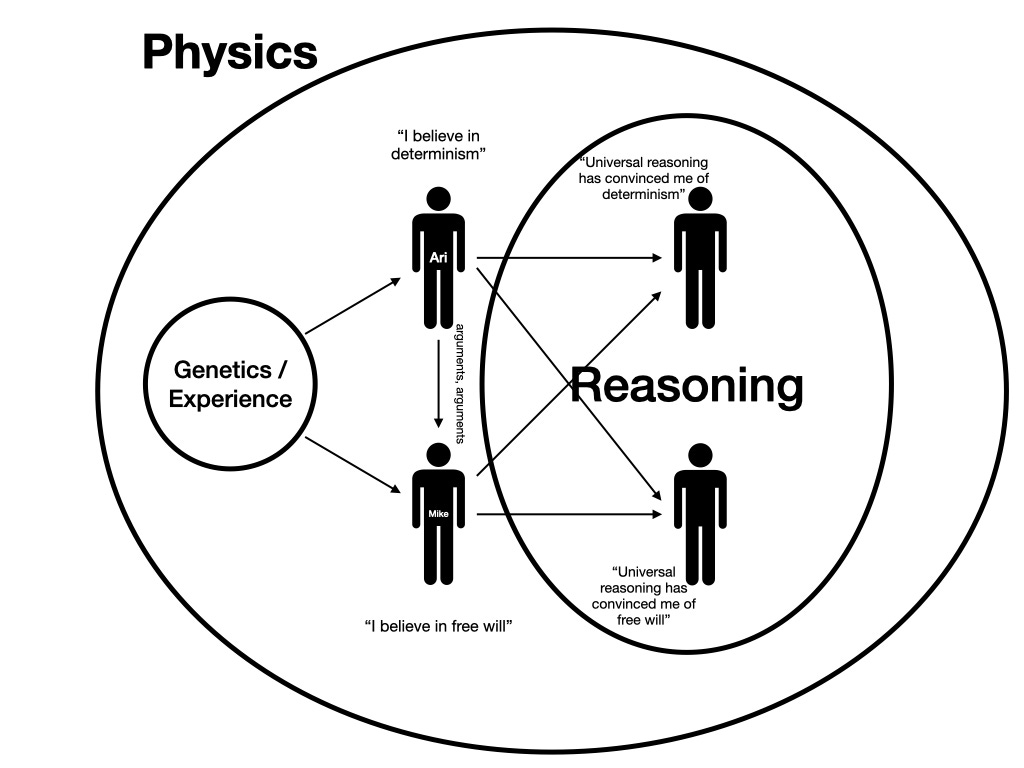

Here’s the picture that Huemer’s intuition is drawing (cf. Thou Art Physics):

But a determinist actually believes in this:

Yes, we’re conditioned into certain beliefs. But my attempt to convince you of determinism is also “destined” to occur, and your reaction to my argument will feel like a choice, but is actually also (probabilistically) determined.2

Huemer’s intuitive understanding is fundamentally incorrect. And as his logic flows from that intuition, the same confusion permeates it all.

Just two assumptions are supposedly needed for Huemer’s argument, and they’re very tame:

He’s arguing against ‘hard determinism’: the belief “that, at any given time, you only ever have one thing that you can do.”

He thinks we should prefer believing true things to believing false things.

I definitely don’t have a problem with the second, but have a small caveat for the first: I don’t think there’s only ever one thing you can do, but instead a fixed probability distribution across many different things. You don’t have any control over that distribution, so you don’t have free will.3 I think this comes out close enough to what Huemer calls “hard determinism” that his argument is relevant to my understanding. Also, he totally fails to even disprove the hard version.

Here’s the proof:

We should believe only the truth. (premise)

If S should do A, then S can do A. (premise)

If determinism is true, then if S can do A, S does A. (premise)

So if determinism is true, then if S should do A, S does A. (from 2, 3)

So if determinism is true, then we believe only the truth. (from 1, 4)

I believe I have free will. (empirical premise)

So if determinism is true, then it is true that I have free will. (from 5, 6)

So determinism is false. (from 7)

As is basically always the problem with logic, words are dumb and hard to understand. Huemer responds later in his post to a common criticism that the ‘should’ in (1) is an epistemic ‘should’, and the ‘should’ in (2) is a moral one. He argues that this doesn’t matter: premise (2), the “‘ought’ implies ‘can’” principle, is valid for whatever ‘should’ you plug into it.

The counterfactual form of (2) is that if you can’t do something, it’s not possible to say you should do that thing. So in the case of the epistemic should: if you can’t know something, it’s wrong to claim that you should know it. But is that really true?

Huemer’s premise (1) is actually a weakened version of the truth-seeking assumption he had us make: not only should we “believe only the truth,” but we should also believe the whole truth. (Cf. every court of law ever.)

That’s not really possible is it? There are certain truths that are totally inaccessible to us, but that doesn’t mean we epistemically shouldn’t know what they are. Some examples:

How many zebras are inside Kenya’s borders right now?

How many trees are within a 6.28 mile radius of your home?

How many grains of sand are in the Sahara?

…

These are all questions with determined, correct answers. We understand perfectly what’s being asked. Epistemically, we should know the true answer to all of them—but of course, it’s just not possible to answer correctly. (Maybe it eventually could be possible for someone somewhere, but it’s really not possible for you.)

Let me further clarify this idea: there are truths that are inaccessible to certain people. An illiterate Sentinelese crab fisher doesn’t know that the English word “apple” has five letters. If you ask him how many letters “apple” has in it, he won’t understand, and he’ll probably just skewer you with his harpoon.

This is what’s happening when you ask someone what they think of free will: they don’t really understand, get panicked and blurt out an answer. For many people, that answer is “I believe in free will.” For many, that answer will always be “I believe in free will” no matter how much context or argument or clarification you give them. They’re not actually capable of disbelieving.

Fundamentally, Huemer is assuming the statement “someone can believe in determinism” is equivalent to “everyone can believe in determinism”—which would imply that everyone does believe in determinism—when actually some people are just wired not to, at least right now. Of course a brain could exist that’s deterministically incapable of believing in determinism, just like a brain can exist that’s deterministically incapable of knowing how many letters are in the word apple.

Yes, theoretically, you could take the Sentinelese man and teach him how to count English letters. But, in reality, his brain will tell him to stab you before you can get through to him. What I’m saying is: there’s a massive array of different brains and experiences to be had on Earth. Obviously there’s some combination that will result in a person truly unable to know a certain truth.

At the very least, he’ll obviously be unable until you show him how to know that truth. Huemer’s current brain and current state of experiences make him incapable of believing determinism is true. He still should believe in it epistemically, and maybe he will in the future, once he has an experience that makes it possible, or once a massive tumor gets removed, or once a massive tumor grows.

To recap: an epistemic “‘ought’ implies ‘can’” principle is flat-out wrong. There are certain unknowable truths—or at least truths unknowable to certain brains—and it’s still totally coherent to say that we ought to believe those true things.

Without the ‘ought’ implying the ‘can’, Huemer’s argument rests on justifying the claim that someone who believes in free will could, with the same set of experiences and the same neuronal array, choose to believe in determinism instead. But obviously, you can’t prove that without begging the question: you’d need to have free will to change your mind without an external cause.

He’d probably claim that when I say he’s question-begging, I’m actually the one doing the begging. That I can only reject willful mind-changing based on my conclusion that determinism is true. But that’s obviously really really stupid!

He’s cel-ing a lot of words and rotating a lot of shapes, but please recall: Huemer is doing a proof by contradiction! He’s assuming determinism is true, and then trying to prove that it’s inconsistent with itself.

“Empirical premise” (6)—“I believe I have free will”—must necessarily mean “I can believe I have free will,” which requires free will to be true, which requires determinism to be false. He sneaks in the contradiction as a “premise” and then pretends like he’s proved it independently two steps later.

The proof is circular. You can’t contradict determinism if you don’t actually follow the implications of determinism being true. When we do follow those implications, the proof is wholly unconvincing:

We should believe only the truth. (premise)

If S should (epistemically) do A, then either S does A, or the current version of S is incapable and S might eventually do A later.

If determinism is true, then if S can do A, S does A. (premise)

So if determinism is true, then if S should do A, either S does A, or S is incapable of doing A right now. (from 2, 3)

So if determinism is true, then anyone who is capable of believing the truth will believe the truth. (from 1, 4)

Michael Huemer believes he has free will. (empirical premise)

So if determinism is true, then it is either true that he has free will, or he is incapable of believing that he doesn’t right now. (from 5, 6)

So either determinism is false, or it’s true and Michael Huemer doesn’t know it. (from 7)

As smart as he is, I’m sure Michael Huemer doesn’t know lots of true things—he probably has no idea how many zebras there are in Kenya—so his opinion alone shouldn’t give you much reason to doubt the obvious case for determinism.

Cover Photo by Jose Fontano on Unsplash

I’m trying to take Huemer’s argument in good faith and on its own merits, so I’m putting the meta-level complaint in the footnotes: Jesus Christ, Mike, maybe if all of the philosophers who ever look at your college-age theory dislike it and argue against it, that gives you some reason to review the literature or revise it. Now, please, allow my almost-college-age theory to predominate.

You’ll notice I’ve also drawn the ‘Reasoning’ circle within ‘Physics’. We have to differentiate this from ‘Reason’ itself—‘Reasoning’ is a thing that a person does which may not conform to perfect logic. I want to leave the door open for determinism being disproved by logic in theory, but clarify that the human process of coming to a belief is well within the physical realm.

I don’t want to go way into it, mostly because I don’t know enough physics to be sure of this all. But basically: quantum theory seemingly disproves perfect physical determinism. Instead, we get wave functions which describe a bunch of different possible states and their relative probabilities. Mostly, this uncertainty only exists in really weird, non-human circumstances, so I think it’s safe to say that physics predicts human brains to be deterministic, if not every single particle in the universe. In essence, the probability distribution for what your brain does in any given circumstance has a standard deviation of 0.000…0001.

More broadly, the Many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics claims that even though some particles behave non-deterministically, they are fundamentally determined. It posits a bunch of different non-communicating parallel universes popping out of each uncertain event, one to represent each outcome. Frankly, I think it’s unnecessary to think of these as literal universes (because that version of MWI is rightly criticized as unfalsifiable and weird), and we should instead just get comfortable with the idea of uncertainty! When I flip a coin and it lands on heads, we can imagine a universe where it landed on tails, and realize that before flipping that coin, both outcomes existed in a fixed probability distribution. Similarly, when a particle’s wave function looks like it collapsed in a certain way, we can imagine a universe where it collapsed some other way, and realize that, in fact, the wave hasn’t really truly collapsed, and there’s been a fixed probability distribution the whole time.