Leave No Trace

A study in institutionalized insanity

1. What Is the Thing?

According to some, there is an “Inside” and there is an “Outside.”

Being Inside is very different from being Outside, and you can tell them apart because Outside is good, while Inside is bad.

You might think that humans are good, given that we're mostly made of the same stuff as Outside. But you’d be wrong! It’s a trick! Inside is trying to fool us into thinking it might be good for humans to go and interact with Outside.

Please, you’ll be begged, don’t fall into this most insidious of traps!

Humans are the very most fundamental manifestation of Inside. Whenever one goes outside, they’ve got to take some very serious precautions to keep from infecting everything with their Insideiness.

This philosophy, broadly construed, is called Leave No Trace, and there’s an advocacy group of the same name which somehow spends $3 million each year spreading its gospel. The gospel consists in Seven Principles, which are:

Plan Ahead And Prepare

This one is less a principle, and more a “no, really, listen to the next six, I’m serious” kind of thing. Very biblical.

Travel And Camp On Durable Surfaces

When you’re getting ready to sleep on the Outside, make sure to pick a really good strong piece of Outside that’s capable of repelling your Insideiness. Don’t try to sleep on a river or a stream or anything; you might hurt it. Aim for grass and/or dirt instead.

Dispose Of Waste Properly

All food is Inside. Please try to keep all of it in your body. Anything that doesn't fit should be stored in your pockets and then thrown away somewhere Inside, where it can be picked up by the garbageman and taken to a different Outside from the one you’re at right now.

Leave What You Find

Outside things like being Outside, where they can be raped and murdered and eaten by other Outside things. Do not disrupt this beautiful tapestry.

Minimize Campfire Impacts

Fire is an Inside thing. If you must have one Outside, please keep it small.

Respect Wildlife

See #4.

Be Considerate Of Others

Odds are, you’re more Insidey than anyone else you’ll ever run into Outside (cf. the friendship paradox). Others are cleaner, better, and purer than you; please defer to them in every respect.

These principles, rest assured, “are up to date with the latest insights from biologists, land managers, and other leaders in [O]utdoor education.”

2. Why Is the Thing?

Certainly there’s some merit to Leaving No Trace.

Manhattan and the Appalachian Trail look very different, they feel very different to be in, and it’s clearly good to be able to see and experience things like the latter when we want to.

And, of course, human impact on the outdoors can be meaningfully destructive. We’ve driven tons of things to extinction before, sometimes very purposefully.

Plus, plastic is super gross! It’s hard for any kind of life other than us to make any use of it, so, yeah, it’d probably be for the best if we keep closer track of where it’s all ending up. It makes sense to keep fires small too—big fires have a nasty tendency to get really big, in ways that can kill people and destroy Inside things too.

Presumably these were all big issues at one point!

For a long while, everyone was very big on Inside, given that we’ve been trying for ~all of history to make Inside a pleasant and clean place. Eventually, we even figured out how to make it bright or dark Inside whenever we wanted; how to pipe in clean water and pipe away all our pee and poo. It was great! Outside sucked relative to Inside! Fuck Outside, why not infect it with some Insideiness?

And so we built stuff! We drove things extinct! We shat all over the place, we slept on the streams, we lit massive fires, and planted farms on the burned-up land.

But then the hippies came along, and they said, “hm, maybe this is bad,”; they said, “hm, maybe Outside is good.” And we elected their great hero, Richard Milhous1 Nixon, and he agreed that Outside was a thing that should be protected sometimes. We had enough Inside already, no need to build more, time to stop the spread.

First, these environmentalists tried passing laws against disruptive camping practices, but they got Don't Tread’ed very hard in response, so by 1990, the US Forest Service had shifted their strategy. They began fighting a PR war; published the 75 principles of Leaving No Trace. Over the course of a decade, realizing this was somewhat insane, they massively consolidated the principles, leaving us, in 1999 with the list of seven we still have today.

3. The Thing Is Bad

Leave No Trace makes sense in a very historical, very contingent sense. We were leaving too much of a trace, it was a very nasty trace, and it could’ve used some neatening-up.

But it’s hard to convince people to change their ways with a campaign like “do 10% less of X, please.” So the USFS and its apologists began making more universalizing, more extreme justifications for why one must Leave No Trace at all.

The only problem: these justifications make no sense!

You’ll encounter them mostly in two slightly-different flavors: indigeneity and naturalness.

How can we tell indigeneity is involved? The land acknowledgments!

The LNT organization itself uses land acknowledgments to “honor Indigenous Peoples and cultural ways of stewarding the land, practiced from time immemorial to this day.” And when I was introduced to Leaving No Trace, we had just walked for about an hour, up to this view…

…when we paused for five minutes to hear about the dozen or so tribes who ever controlled any part of northwestern New Jersey, and how they’ve faithfully stewarded the land (since time immemorial).

This was a) very funny and b) a nice break, but it was also pretty stupid. I’ve written before about my thoughts on indigeneity in general, but to briefly recap:

Everyone is from somewhere. It’s not clear why people from northwestern New Jersey are any more indigenous to there than I am to Belarus, or Israel, or sub-saharan Africa. The timescale that’s allowed to count is very gerrymandered!

Regardless of whether I am an indigenous Belorussian, there’s no reason it should entitle me to control or ownership or stewardship of any given piece of land. The same goes for more-generally-accepted kinds of indigeneity.

This is the case even if some culture is particularly well-adapted to living in one place. These days, we can almost certainly do better with science!

It’s important to mention this because people will often make reference to various historical scenarios (e.g., Squanto, the Secrets of Our Success root-boiling thing, etc.), but this isn’t a good argument! We know a lot more about how nature works now, and I would trust a PhD in environmental science to preserve a forest much better than some old Indian chief’s great-great-great-great grandchild.2

It’s also worth mentioning that indigenous people were never all that great at stewarding natural areas in ways that Left No Trace.

I mean, they lived off the land! Sometimes this is presented as some kind of mystical-communion-with-the-land, but, you know, that’s not a real thing! It was just people interacting with nature, killing and burning and using all the different kinds of things they found there.

This is fine, but it’s not very conservationist, and it’s not clear why we should worship it above the kinds of killing and burning and using we do for industrial purposes. (If anything, maybe we should prefer the industrialized version; it’s way more efficient!)

On naturalness more broadly,

is very good.In short, the line between what we consider natural and what we consider human-infested is very thin and very arbitrary.

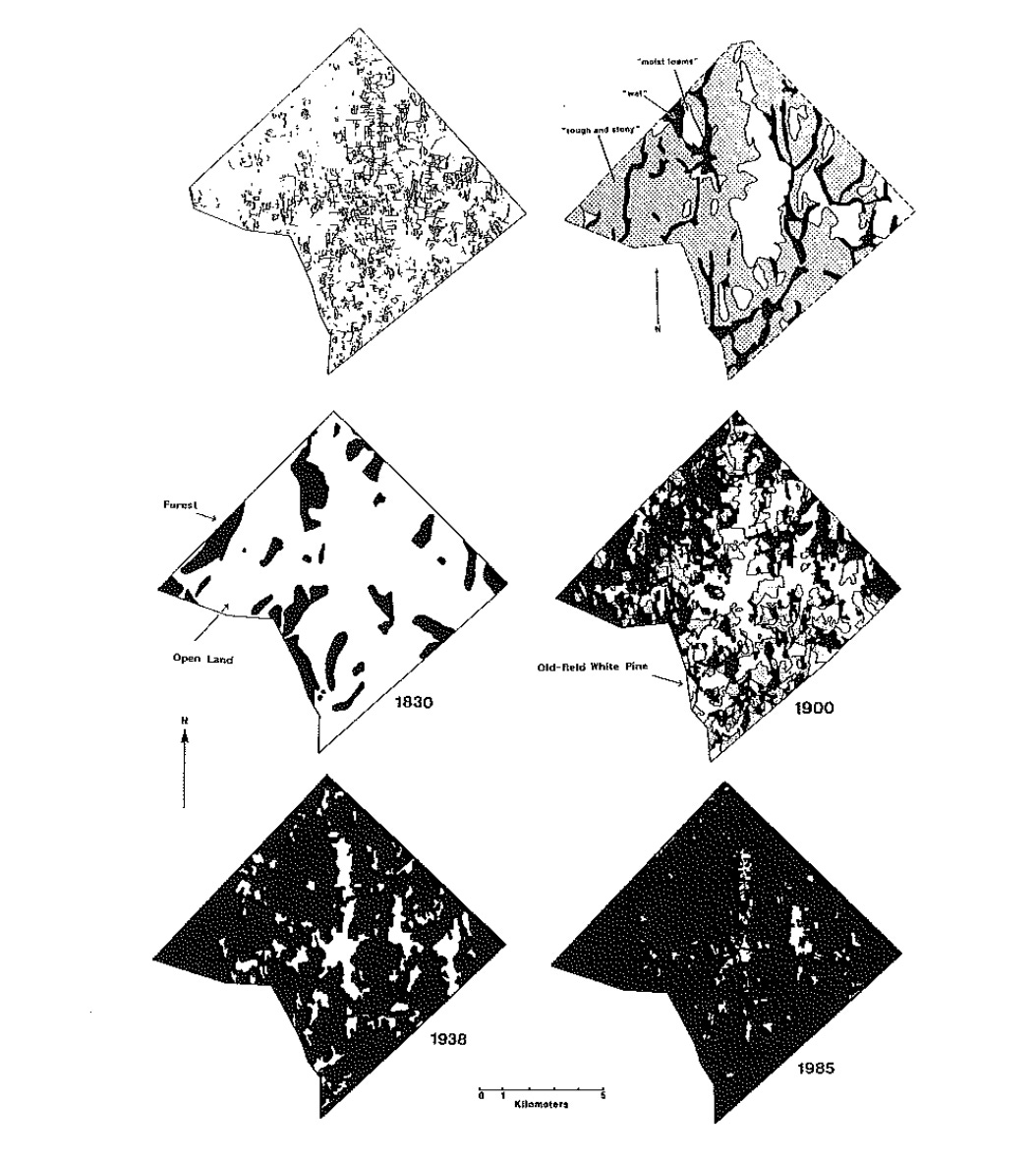

For instance, the New England forests where I was exposed to all this Leaving of No Trace are not very old; not very pure and untouched. In some cases, they were barren prairieland as recently as the 19th or even 20th century.

As land use practices changed, the trees came back. This is nice, and I’m all for keeping the trees around, but we shouldn’t pretend they’re something very ancient and unapproachable. We’ve left very big traces before, and they bounced back! No need to panic.

It’s also important to note that things which are less-human-infested aren't obviously morally better than things with more artificiality.

The killing and raping that goes on in the animal kingdom isn’t great. Lots and lots of suffering happens in nature, so why should we revere it? I’m not saying we absolutely must destroy it all—but we definitely ought to be more skeptical that keeping things exactly as they are is optimal.

I don’t mean to suggest that we should forget all about our Trace, and start throwing plastic around wherever, and starting forest fires just for the hell of it. These things are still bad!

But obviously this has gone too far. It’s crazy!

According to LNT, you can’t dig a trench around your tent. Why should this be! It’s 100% impossible to sleep with a wet ass; asking people to try to do this is unbelievably cruel.

In a similar vein, why can’t I take a rock or two with me? What’s the harm, if I find a really cool one, and want to use it as a paperweight or whatever?

And why can’t I chuck an apple core way out into the forest? Far away from the trail! With no risk of attracting bears! What’s wrong with that?

Most importantly: why, in God’s name, should I have to take my toilet paper back home with me?

These people are out of control.

4. Where Does the Thing Come From?

There’s a broader pattern at play here. One in which things that are contingently, historically, specifically-in-one-situation good ideas grow way beyond whatever size they ought to be.

The story seems to go:

Have a good idea with a boring and unappealing justification.

Come up with an ad-hoc justification that makes the idea seem very noble, wise, and generally awesome.

Movement begins attracting true believers.

True believers take over movement and expand it way beyond its initial, unattractive, boring, good intent.

Movement starts doing crazy shit.

A lot of things behave this way, especially activist groups.3 A few prominent examples I can think of are:

Pro-palestine activism. Many people get into this because Israel treats Palestinians in ways that are clearly awful. But the issue is complicated and a principled stance like “everyone has to shape up and stop chucking bombs at each other” isn't very sexy, and so pro-palis adopted a bunch of very cool and noble talking points instead. Claims about israel being an apartheid state, and Hamas being freedom fighters, and so forth. Predictably, this attracted true believers, and now the movement only ever does crazy shit!

Wokism and identity politics. There’s a lot of inequality in America, much of it on racial and identitarian faultlines. It would probably be good to have less of this! But to get less in ways that aren't zero- or negative-sum would be difficult and boring, would involve lots of zoning reforms and takings-on of personal responsibility. So a new, more awesome story was invented. The early woke theorists claimed that America was deeply racist in every way, it was a hit, true believers joined up, and then they started doing only crazy shit.

The reaction to wokism and identity politics. American elite culture definitely went a bit kooky. It would’ve been good to undo some of this kookiness, while still being compassionate and decent to the downtrodden. But that’d be so boring! It was way more fun to talk about Cultural Marxism and rotten institutions, even some of the principled-civil-libertarian-Chris-Rufos of the world became true believers, and now the anti-woke only ever do crazy shit.

I think there are various ways for movements to not do this to themselves. One very good one is to stay boring. It’s nice to have influence, but it’s not the movement that should have the influence, it’s whatever policies the movement has decided are good. In practice, this probably means doing less in the way of recruitment and community-building, and more in the way of actual-stuff; lobbying and researching and writing of white papers.

The problem comes when multiple movements are all trying to accomplish the same end. The very-scrupulous-and-careful activists will focus on making boring claims and not-growing, and then someone else will come along saying interesting and attractive things, and trying to increase their influence. The defector will get more support and more money and more airtime, and we’ll see way more of him than anyone else.

The result of this is well-described by Scott Alexander in The Toxoplasma of Rage—in short, it’s quite bad!

I don’t really know how to fix this. Maybe it’s possible to get activists to sii that defection doesn’t actually benefit their cause, it only benefits their profile? But this assumes that every activist cares more about what they claim to care about than their own fame and success, which is insane.

Or maybe it’s possible to be sane and sexy? As far as I can tell, this is the point of the Abundance Agenda—to make rezoning and neoliberalism cool again. I don’t know whether this will work, but I think it’s fairly unlikely; Gavin Newsom’s pulled way ahead in the 2028 Democratic Nominee prediction markets, but only once he started trolling Trump on Twitter. It’s quite a bit sexier than industrial policy, but certainly not saner!

Toxoplasmic defectors stay winning, and I’m out of ideas.

I realize that this post has gotten away from me somewhat.

So let me now conclude, very synthesistically: Neither will I carry shit-covered toilet paper along the Appalachian Trail with me, nor will I ever vote for Gavin Newsom.

A man must stick to his principles, and these are mine.

Yeah, no “e.”

This is really saying something, because I tend to consider PhDs in environmental science to be real dumbfucks. (To those who are PhDs in environmental science and agree with the rest of the essay: this is a joke. To those who disagree: I am being very serious right now; you are a dumbfuck.)

I don't think this pattern has a name, and I don't really have any good ideas. I'll probably be referencing it a lot in the future, so if you can think of something snazzy to call it, please let me know.

I'm thinking something in the neighborhood of “self-capture” (compare to “audience capture”) but that really sucks, so I dunno.

Agree with many points. However: “But what if everyone did The Thing?..” -Some European philosopher. That is to say, a lot of our problems are emergent, when the multiplier is 100,000 or 10,000,000 or 1,000,000,000 people doing any given thing. My limited understanding of psychology is that humans are calibrated for individualistic / family-scale responses, an inheritance of 500,000+ years of living at most in groups of < 50, and so (most of us are) really bad at thinking at scale. I saw some of the very early episodes of Sesame Street on YouTube… the kids were running amidst utterly disgusting piles of city detritus strewn about the beach! That said, I do get the broader points about recruiting for causes, incapacitation by dumb shit, etc. (Also, I really dislike bugs and really like hot showers!)

I like the Big Point you’re going for about how goals/talking points warp into their most extreme version… but I think you picked a real bad example. I posted a reply.