Here is an insane thing I saw on the internet recently:

A bunch of Philadelphia city employees went on strike for a week, including all the garbagemen. Many locals were upset about there being a bunch of garbage everywhere, and this woman took initiative, seized on the opportunity, and likely made a solid bit of money off the strike. And probably also helped lots of the people around her who disliked living among piles of garbage.1

For this, the union called her a “scab.”

1. This Is Not Scabbage

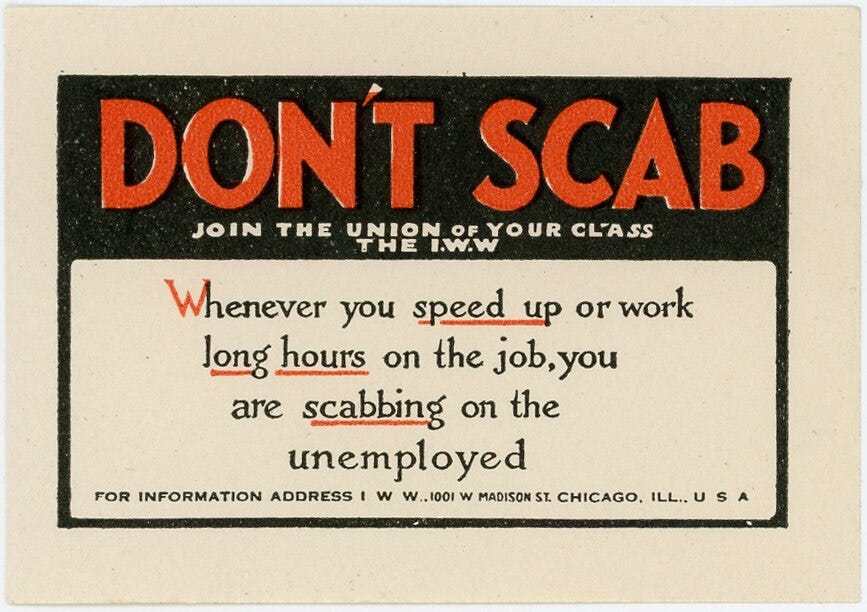

In the group-struggle over the division of the joint-product, labor utilizes the union with its two great weapons,—the strike and boycott; while capital utilizes the trust and the association, the weapons of which are the blacklist, the lockout, and the scab. The scab is by far the most formidable weapon of the three. He is the man who breaks strikes and causes all the trouble.

The woman in question, plainly speaking, didn’t break the union’s strike!

Employees of the city were in negotiations with the city to receive a new, better contract from the city.

A scab, then, would be someone who went to the city and asked to be employed in the strikers’ stead!

This woman did no such thing—she put together a totally separate service, paid for by her neighbors, without any connection to the capital which would’ve been seeking to quash the strike with scabs.

From what I could tell, this was the most intuitive objection to the union’s tweet. For instance, the top reply:

When we hear “scab,” we think of some slimy piece of shit crossing a picket line—not an enterprising woman helping her neighbors clean up the streets.

Unfortunately, this opinion is pretty obviously wrong, and in fact…

2. This Is Scabbage

Under the definition that a scab is one who gives more value for the same price than another, it would seem that society can be generally divided into the two classes of the scabs and the non-scabs. But on closer investigation, however, it will be seen that the non-scab is almost a vanishing quantity. In the social jungle everybody is preying upon everybody else.

— Jack London again

The strikers’ bargaining power is based on how annoyed they can make their bosses.

How annoyed the bosses are is based on how much shit there is in the streets.

The amount of shit in the streets is based on how little garbage is being driven off to the dump.

…And this woman is driving garbage off to the dump! The strikers, presumably, would like to provide somewhat less than a carload’s worth of garbage-pickup for a price of $25—otherwise they’d be running the same racket. Since the woman is offering a greater value for the same price, she’s a scab!

Simple as that.

3. Scabbage Is Good

to scabbing, no blame attaches itself anywhere. All the world is a scab, and with rare exceptions, all the people in it are scabs. The strong, capable workman gets a job and holds it because of his strength and capacity. And he holds it because out of his strength and capacity he gives a better value for his wage than does the weaker and less capable workman. Therefore he is scabbing upon his weaker and less capable brother workman. This is incontrovertible. He is giving more value for the price paid by the employer.

— still Jack London

Why do we find it reflexively weird and bad to call this woman a scab when she so clearly is one?

Because “scab” is quite negatively-valenced! Here, for instance, is Jack London:

The sentimental connotation of scab is as terrific as that of “traitor” or “Judas,” and a sentimental definition would be as deep and varied as the human heart.

But as it’s technically defined, there’s really no difference from the slimy, picket-line-breaking scab we imagine, and any cunning, entrepreneurial scab who attempts to provide some good or service for a better price.

Markets are built on scabbage—on responding to demand efficiently; via sliminess, hard work, technology, or whatever else.

On measure, this tends to be a good thing! Every laborer who feels threatened by scabbage is also a consumer who benefits from it. And every capitalist who worries about being undercut by his competitors is also a consumer who likes it when he can buy goods for cheap!

The fundamental error of trade unionism is its pathological nearsightedness: the idea that scabs in my particular industry are evil and bad, but scabs among capitalists or among other laborers can do all the scabbagery they’d like.

From the perspective of a trade unionist, it makes perfect sense! It’s a rational appraisal of what benefits their interests most, and it’s useful information for the market to aggregate.

However! That doesn’t make it a rational appraisal for anyone else. And so no one else should be compelled to act in accordance with it!

Scabs have a right and a duty to scab when they want to, and the public has a right and a duty to let them do it. When unions call for boycotts, solidarity strikes, or attacks on scabs, they throw everything askew—they deserve exactly as much bargaining power as the market assigns them, and not a bit more.

Unions are probably fine in their most limited conception—as simple Moloch-mitigating machines—but unacceptable as political (much less violent) forces.

Addendum: Jack London Appears to Be Sort of a Dumbass

I’ve quoted a fair bit from London’s essay, “The Scab,” which appeared in The Atlantic in January of 1904. It’s generally entertaining, well-written, and perceptive, but its conclusion is this:

It is not good to give most for least, not good to be a scab. The word has gained universal opprobrium. On the other hand, to be a non-scab, to give least for most, is universally branded as stingy, selfish, and unchristian-like. So all the world, like the British workman, is ‘twixt the devil and the deep sea. It is treason to one’s fellows to scab, it is treason to God and unchristian-like not to scab.

Since to give least for most and to give most for least are universally bad, what remains? Equity remains, which is to give like for like, the same for the same, neither more nor less. But this equity, society, as at present constituted, cannot give. It is not in the nature of present-day society for men to give like for like, the same for the same. And as long as men continue to live in this competitive society, struggling tooth and nail with one another for food and shelter, (which is to struggle tooth and nail with one another for life), that long will the scab continue to exist. His will to live will force him to exist. He may be flouted and jeered by his brothers, he may be beaten with bricks and clubs by the men who by superior strength and capacity scab upon him as he scabs upon them by longer hours and smaller wages, but through it all he will persist, going them one better, and giving a bit more of most for least than they are giving.

In essence, London appears to think that a market-based system of economics will always generate scabs (which is true), that this is bad (which is arguable), and that some other magical system exists where this won’t happen (which is laughable).

The giving of “like for like”—or “equity,” as London puts it, meaning something far different from how the term is used today—is, I think, quite achievable in a capitalist system. In fact, this is what markets exist to do! To take lots of people with lots of different ideas and abilities, and to put them into jobs where their wages reflect the value they deliver, eventually, to a consumer.

This involves lots of imperfection and jostling around, which appears to be London’s big issue with it, but, hell, there’s really no better alternative! Set aside, for now, all the incentives for innovating and creating new technologies that are an inherent and incredibly valuable feature of scabbagery.

Let’s just consider the question of whether a socialist system would have scabs at all—the answer, of course, is yes! In, for instance, a Soviet model of communism, everyone gets roughly the same provisions as everyone else. In essence, wages are pretty constant across society—but the value supplied by different people is vastly different! So you’ll end up with lots of scabbing free-riders who do very little work, and plenty of overworked laborers being scabbed-upon.

A central planner in such a system will probably try to reshuffle provisions so everyone gets some amount more proportional to his contribution—but how, exactly, should he do this?

The issue with socialism is that no one’s ever been able to come up with a better answer than “do markets, but with extra steps.”

The question remains: if you dislike living among garbage, why live in Philadelphia? But I digress…

To the extent that people like this girl are undermining the union's bargaining position--they're making it less unpleasant for people to live in a Philly without trash pickup, and so lessening the pressure on the city to give in to the union's demands--they're "scabbing" in the sense that matters to the union. But like you, I don't see why this ought to resonate with third parties. Why should we as outsiders think that whatever the union's demands, the city ought to give in to them, and so any action that makes that less likely should be condemned?

I think it's a reflexively pro-labor stance that leads people to oppose "scabbing". And in my judgment, that's a really hard stance to justify when it comes to public sector unions, for all sorts of reasons that won't fit in a substack comment. Imagine a striking police department calling people who join ad hoc neighborhood watch patrols "scabs". Would condemning those "scabs" seem sensible? If not there, what's the difference when it comes to trash pickup?

It depends a lot on what exactly the union is demanding. Suppose the city was treating them terribly - unsafe working conditions, wage theft, harassment and abuse. Then, as a sympathetic observer, I might want to show support by not lessening their leverage. But if their demands are esoteric or puzzling, then I'll have less sympathy for making everyone else suffer to meet them. I think more people should be willing to base their opinions on any individual case of "scabbing" based on a case-by-case evaluation of what the strike is demanding.