1. Is Having Fun Wrong?

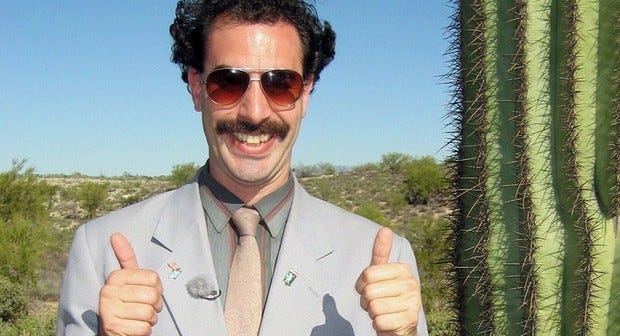

I’m a big fan of Sacha Baron Cohen’s Borat! Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan.

It’s a really strange movie—released in 2006—but it’s probably best characterized as a sort of comedy-documentary.1 Baron Cohen adopts a fictionalized role as Borat Sagdiyev, a Kazakh journalist tasked with learning about what makes the “US and A” such a great and wealthy nation.

Most of the film is made up of short, unscripted scenes in which Borat interacts with real, normal people while acting like a total weirdo. He’s got a crazy accent, and is extremely antisemitic, homophobic, and sexist—but he does it all with a disarmingly friendly disposition, yielding consistently bizarre results.

Every single one of these vignettes is hilarious—it’s really an excellent movie. Often, when Borat asks something awful and ridiculous—like, “What is the best gun to defend from a Jew?” or “If this car drive into a group of Gypsy [sic], will there be any damage to the car?”—he gets a serious, matter-of-fact answer: “I would recommend either a 9 millimeter or a .45”; “It depends on how hard you hit ‘em.”

To me, this is funny.

To Baron Cohen, it’s a statement—here’s a bit of his interview with Rolling Stone in 2006:

Borat essentially works as a tool … By himself being anti-Semitic, he lets people lower their guard and expose their own prejudice, whether it’s anti-Semitism or an acceptance of anti-Semitism. ‘Throw the Jew Down the Well’ [a song performed at a country & western bar during Da Ali G Show2] was a very controversial sketch, and some members of the Jewish community thought that it was actually going to encourage anti-Semitism. But to me it revealed something about that bar in Tucson. And the question is: Did it reveal that they were anti-Semitic? Perhaps. But maybe it just revealed that they were indifferent to anti-Semitism.

See, Baron Cohen, like all artists everywhere all the time, thought pretty highly of the philosophy behind his project: “he presents himself as a moralist, a liberal idealist.”

That quote comes from an excellent 2011 paper by Randolph Lewis: “Prankster Ethics: Borat and Levinas.” It was published in Shofar, a Jewish philosophy journal, and Lewis admits that he’s being a bit of a “spoilsport,” dissecting a comedy with Emmanuel Levinas’ 20th-century philosophy of the Other.

But given that Baron Cohen “frames Borat as a response to the Holocaust” in that same Rolling Stone interview, Lewis figures it’s fair game.

And he really brings his best!

Lewis writes that the entire project was steeped in deception: “Baron Cohen and his producers treated their interviewees like ‘marks’ in a con game.” They had subjects sign legalese-heavy release forms that amounted less to “informed,” and more to “deformed consent.”

And it looks like real harm was done too! One of the most famous scenes from the movie involves Borat attending a fancy Southern dinner party, excusing himself to use the restroom, and then returning to the table with a bag of his poo. Lewis quotes one of the scene’s regular-person participants, Borat’s “etiquette coach,” who wasn’t so amused:

Lives have been ruined by this comedy … I realize that some people will watch the movie and find it funny, but for the people who were duped into appearing what happened was anything but humorous.

Obviously this sounds pretty overdramatic, but the woman in question apparently felt damaged enough to “file a complaint with the California Attorney General.” It never went anywhere, but it sure seems like Baron Cohen did her some kind of harm!

Lewis’ final and most damning critique is that Borat fails to be a useful social commentary by design. Drawing on Levinas’ “ethical project, one that proposes radical humility and profound responsibility toward the Other,” Lewis argues that Baron Cohen’s supposed-moralism is shockingly hollow and self-centered:

Cohen puts on the persona of Borat as if he has found a ring of invisibility that exempts him from social justice. With his elaborate persona concealing his own face, Cohen disappears from view without seeming concerned about the impact of his deceit on his interviewees. If the deception has wounded them on-camera (or later), Cohen offers no solace other than to point to the ethical motivations behind his work. Rather than trusting the other, he skewers from behind his comic mask, convinced that he is going out “into a crowd of people who hate you,” as he told Rolling Stone. In a manner that turns Levinas on his head, Cohen substitutes hilarious sadism for selfless humility.

I found this a pretty compelling critique—and it also reminded me of another piece I’d read recently, “The Cruel and Arrogant Gaze of Nathan Fielder’s ‘The Rehearsal’,” by Richard Brody in The New Yorker.

The Rehearsal is an obviously Borat-inspired comedy, and it’s also ridiculously good (even if Fielder’s conceit gets the best of him in season 2). It’s a less politically-motivated project than Borat, but Fielder’s got a lofty vision nonetheless—Brody summarizes:

Fielder’s idea is that behavior is predictable and that he himself is good at predicting it. His volunteers come to him with a problem; his plan is that, when these real people rehearse, with the help of actors, the scenarios involved in these troubles, they’ll be able to anticipate possible outcomes and thus bring about their desired one.

But it’s a comedy, and so of course everything spins a bit out of control. Even as it does, Fielder remains stoic and utterly convinced of himself—sure that his “rehearsals” can help people overcome their worst anxieties.

To my eye, the tension between Fielder’s unwillingness to adjust and his subjects’ increasingly unpredictable behavior creates drama, and it also creates a dry, subtle sort of comedy.

Brody, on the other hand, is disgusted:

[Fielder] revels in his own thoughts as he tailors the conditions of his subjects’ lives to fit his storytelling, largely through his own voice-over. Fielder’s main real-life stake is the one onscreen: making the show a success. The vanity and the ambition of “The Rehearsal” are its driving forces. Fielder can’t relinquish control; his obsession with details, with predicted outcomes, suggests his very failure as a filmmaker—the failure to find a dramatic form for the full range of the series’s implications and experiences. If the series is meant to be comedy, so much the worse, for making light of problems that matter to the participants—and for making even lighter of the deceptions to which he subjects them.

Brody appears to have basically the same problem with The Rehearsal that Lewis does with Borat: there’s something off about these pranksters. Their deceptions are cruel; their gazes are objectifying and othering; their projects undermine the stated goals.

As far as I can tell, we can break their criticisms into three broad categories:

Continental handwaving about objectification and superfluity—to paraphrase Brody: Sacha Baron Cohen and Nathan Fielder look the Look at the people they film, but don’t seem to see them.

Actual harm caused to subjects via deception (i.e., the subjects are compelled to say things wouldn’t otherwise have said, or are somehow hurt by the inherent act of interacting with someone who’s being dishonest).

Privacy violations (especially in the Borat case) where misleading or overly legalistic language was used to deceive participants.

Seeing as I think rather highly of myself, I’m gonna do the whole chiastic thing and go through these in reverse order.

2. “How Dare You Publish Footage of That Thing I Did While Knowingly on Camera!”

I’ve written before about my skepticism that very many people actually care about privacy in a principled way. As far as I can tell, they mostly become outraged only after the fact—only once they start to feel embarrassed about what everyone saw.

I think this because, if it really mattered to you, you would read the damn contract! Actions speak louder than words, and even when release contracts are made crystal clear, most people just sign them no matter what. An excellent example of this comes from Nathan Fielder’s earlier, similarly-prank-ish show, Nathan For You. At one point, even though “it’s not entirely legal,” Fielder secretly films a number of customers at a diner using the bathroom (just their faces!). And when they come out, he’s standing there with a release form ready: “we were filming you in the bathroom with a hidden camera,” he explains. “To show the customer experience.”

We see three reactions:

The first man says, amused, “Oh, really?” He asks which part of him was filmed; when Fielder reassures him that “your private parts won’t be shown,” he happily signs and sits down for a meal.

The second man is mad. He rants for a little while, threatens Fielder, and the camera cuts to…

The third man, who, when informed that he was being filmed, says “Oh, okay.” When Fielder tells him, “We need to get you to sign this release so we can use the footage on national television,” he shrugs and says “sure!”

A few things to note: First, bathroom-filming is as privacy-violating as it gets. Like, really, try to come up with something that’s more invasive, but technically legal to broadcast nationally if the subject agrees to release the footage. Second, the men’s reactions are very polar and instinctive: numbers 1 and 3 accept what’s going on and are receptive to Fielder’s request. Man number 2 is instantly hostile, and totally categorically rejects Fielder: “I don’t care whatever [body part, presumably] you want to use,” he says. Finally, it’s worth noting that the second man is super European-sounding. Americans have no real problem signing away their rights for a shot at 15 minutes of fame; Europeans pass laws like the GDPR.

Of course, the bathroom situation is pretty different from what’s going on in Borat! The Nathan For You release form is straightforward and clear; Borat’s producers variously told subjects that the footage was for a “Belarus TV station,” a “Kazakh journalist,” a “documentarian [trying] to help women in Third World countries,” and a “documentary about foreigners learning how to drive.”

But in the release, they wrote that the subject “is not relying upon any promises or statements made by anyone about the nature of the Film or the identity of any other Participants or persons involved in the Film.”

So how could it be that signing the form represented a revealed preference (or “informed consent”)?

Well, at a certain point—usually when you turn 18—you become responsible for reading the documents you sign. Every single subject met Borat, talked with him in front of a camera, and then were asked to sign a form which said “we can use that footage however we want.” And they signed the form! That’s consent, regardless of whether some interpersonal deception went on.

If you still feel a bit icky about this, consider that there couldn’t be a movie at all without some degree of deception. If you go in and say “we’re gonna have an undercover comedian come in and prank you, so act natural,” your movie will suck! So the filmmakers fell back on a foundational organizing principle of our society: that is, the idea that mature adults have an individual responsibility to read the contracts they sign, regardless of how pleasant the person asking them to sign has been.

In The Rehearsal, Nathan Fielder acknowledges that this sort of deceptive-consent might be awkward when he assumes the role of one of his own acting students. In one scene, he (as the student) looks around and sees everyone else signing the release contract for HBO. Even though he feels a bit odd about it (why would he need to sign a release to be in an acting class?), he sees everyone else signing, so assumes he should just get over himself and do it too.

But, again, I will say: You are a grown-up person, with full rights over how your image will be used. If it’s just the awkwardness or financial cost of saying “no” that’s too much for you, you’re still making a free decision to sign the contract. If the state legal apparatus were empowered to come in and void any contracts that would’ve been a bit awkward for one party to walk away from (and I’m not talking about actual full-on extortion; I’m talking about these little social pressures we all feel sometimes), that would be really messed up. We trust each other to act in our own best interests—that’s really the foundational principle of tort law.

And, again, to the vast majority of people, I cannot emphasize this enough, privacy really doesn’t matter.

We sign away these rights for the sake of convenience all the time—probably whatever device or app or browser you’re reading this post on knows that you’re reading it, and you signed away the right to privacy over that without batting an eye. Appeals to privacy rights are very rarely a matter of principle (basically Stallman & Snowden are the only two examples ever, and even the latter was more about possible-authoritarian-consequences than personal-privacy-for-its-own-sake), and generally just post-hoc reasoning about some other harm that’s been felt.

3. “How Dare You Do Me Reputational Harm by Publishing Footage of That Thing I Did While Knowingly on Camera!”

As I see it, there are a couple distinct classes of alleged real, material harm that pranksters cause: “you exploited me” and “you tricked me.” These are, in fact, meaningfully distinct, and it’ll probably help to see examples of each.

You Exploited Me

This is a line championed mostly by the residents of Glod, Romania, a small village caricatured as “Kuzcek,” Borat’s backwards Kazhak hometown. A couple of them sued for $30 million in damages after they were upset by the movie’s portrayal of themselves and their town.

One villager, qtd. in (Lewis 2011), said:

We endured it because we are poor and badly needed the money … But now we realize we were cheated and taken advantage of in the worst way.

But is that even really true?

According to the Los Angeles Times, the production paid more than $4 a day to each participant. That sounds pretty meager, but it’s more than double what the Romanian Film Office had suggested. They also donated $10,000—half of it coming from Sacha Baron Cohen personally—to a local school, which used the money to buy computers.

I guess my broader point is this, and it’s gonna come down to personal responsibility again (the title of this post is no accident): “exploitation” is sort of a ridiculous term. Yeah, sometimes the choices you have to make feel bad, or it seems like college interns should be getting paid to make coffee runs or whatever—but scarcity is an unfortunate reality, and sometimes you just have to choose the less-bad thing.

What’s the alternative to Borat coming through town? No one makes any money, the school has no computers, and Glod never gets any tourists! Even if some villagers feel ashamed—which, by the way, they shouldn’t; none of them were named or defamed personally or anything—they’re undoubtedly better off.

The Glod residents’ lawsuit was soon thrown out; the presiding judge commented that “[their] case would need to make more specific allegations if it was to be successful.” In other words: no real harm was done.

You Tricked Me

This complaint’s epitomized by another lawsuit: one filed by three South Carolinian frat brothers.

In Borat, they were filmed expressing their wish to own slaves, and lamenting the fact that minorities hold all the power. Which, you know, is disgusting and insane!

When their disgusting and insane views were played to the nation in theaters, the three sued in search of damages for “humiliation, mental anguish, and emotional and physical distress, loss of reputation, goodwill and standing in the community.”

In other words, they thought “Oh shit, now everyone knows that we’re assholes; Sacha Baron Cohen is to blame.”

Clearly, this is silly. If you’d like to be perceived as a good person, you’re responsible for being a good person, even if you’re interacting with someone who isn’t forcing you to be. Again, these guys saw the cameras and signed the releases—there’s really no excuse!

Remember, this is the point of the movie for Baron Cohen—to goad people into exposing their worst and most vile beliefs. He didn’t put the words in their mouths—they came out quite naturally.

I’d also be remiss not to mention Matt Walsh’s Am I Racist? here, a similarly conceived project which lampoons the crazies on the other end of the political spectrum. Its most incredible scene features famed antiracist grifter Robin DiAngelo—after Walsh pays $15,000 for the chance to interview her, he’s able to convince DiAngelo to pay reparations to his black producer, in cash, on the spot.

This sort of stunt is common practice on both sides—it’s instinctive to laugh at the stupidest and worst fringes of the Outgroup.

Not only that, it’s been accepted practice for millenia—in the Book of Genesis, Joseph pranks his jealous and murdery brothers to see if they’ve really reformed. He, by then the Vizier of Egypt, recognizes them, and seeing that they don’t recognize him, says:

By this you shall be put to the test: unless your youngest brother comes here, by Pharaoh, you shall not depart from this place!

Let one of you go and bring your brother, while the rest of you remain confined, that your words may be put to the test whether there is truth in you. Else, by Pharaoh, you are nothing but spies!

Joseph, of course, knows that this “youngest brother” is Benjamin—the only one related to him maternally, and their father, Jacob’s, favorite. He knows that when all the brothers go back home and tell their father that they need to take Benjamin to Egypt, Jacob will say, “It is always me that you bereave: Joseph is no more and Simeon is no more, and now you would take away Benjamin. These things always happen to me!” (Genesis 42:36).

All the drama goes on a while longer, but eventually Judah, the fourth-oldest brother, steps forward and offers to sacrifice himself in Benjamin’s place. Seeing this, Joseph is convinced that his brothers have reformed themselves, he gives up the charade, and everyone gets to be happy and rich in Egypt. Judah, specifically—in recognition of his most virtuous response under the prankster’s pressure—gets blessed super hard shortly afterward. Jacob, before dying, tells him: “You, O Judah, your brothers shall praise; Your hand shall be on the nape of your foes; Your father’s sons shall bow low to you” (Genesis 49:8).

The three frat boys, in contrast, caved shamefully under a prankster’s pressure. They’re more deserving of the fate of Reuben, Jacob’s firstborn: “Unstable as water, you shall excel no longer” (Genesis 49:4).

Those who performed more Judah-ically deserve praise—like Borat’s driving instructor, who calmly informs Borat that, in America, women must give their consent to engage in sexy times. “That’s good, huh?” he says, even in the face of Borat’s ridiculous assertions to the contrary.

In an interview with The Baltimore Sun on his role in the movie, the instructor soberly registered his disappointment that other drivers were put at risk, but also “declared the film ‘very funny,’ adding: ‘Laughter is good for the world’.”

Similarly, in The Rehearsal, Nathan Fielder’s first mark, Kor Skeete, occupies an impressively dignified role. Though Richard Brody’s New Yorker article suggests it’s problematic that the on-screen “Nathan shows no interest in what Kor thinks of being deceived,” Skeete himself didn’t seem too upset when interviewed by the same magazine. (His singular [bizarre] complaint: “I lost my cool card because I admit I go to trivia.”)

Of Skeete, one Rehearsal fan on Reddit said:

I genuinely like Kor. He seems like a good dude to hang with.

So I’m glad he has had a positive experience from the show and the reaction to it.

The comment received 150 upvotes.

It looks like this sort of comedic pranking rewards the virtuous and thoughtful, but punishes the rash and despicable. That’s pretty good! It’s certainly better than things like conventional reality TV, which routinely reward unvirtuous dramatic behavior, while mostly ignoring anyone who’s well-adjusted.

Of course, blind retribution against bad people, while admittedly often cathartic, is also often extremely bad. Is that what’s going on here? Does pranking damage the quality of the national conversation? Is it wrong to caricature the Outgroupers, with their wildly different views?

4. “How Dare You Superfluously Objectify My Antisemitism!”

Right, well the big issue in both the criticisms from the top is a spiritual one; the sort of thing I’d usually abhor: Nathan Fielder’s “Look”; Sacha Baron Cohen’s failure to “humanize the Other.” At least in the latter case, though, the spiritual language is mostly just a fancy coat of paint on what’s really a very grounded and pragmatic point: people are complicated, their beliefs are too, so we’re not gonna get anywhere useful with cartoonish exaggeration.

There’s a lot of truth to this. I don’t think Borat is an enduringly impressive political work, exposing the rot of latent American antisemitism and homophobia, as much as Baron Cohen might’ve wanted it to be.

But it’s still a hilarious movie! It’s fun and it’s good and I like watching it.

Similarly, even Am I Racist?, with its obvious political slant, is mostly just a good, fun romp. By the time it was released, we were basically over the hump of antiracism: the racial reckoning was over and the left had mostly calmed down (or at least directed all its vitriol elsewhere). We knew Robin DiAngelo’s ideas were bad; making fun of her was still reductive, sure, but it’s not like there was much deep debating left to do. Matt Walsh calls himself an entertainer, and I’m inclined to agree—Am I Racist? is entertainment, not serious, illuminating commentary.

There’s an all-too-common tendency to overestimate the importance of comedians. They themselves do it, columnists do it, hell, even political scientists do it.

had an excellent post on this recently:I don’t think that jokes will take down Trump. I’ll still make them, because making jokes is what I do, but I’m under no illusions that if I cook up a wisecrack with just the right amount of sass, insight, and bawdiness, Trump will lose power.

In the first season of The Rehearsal, Nathan Fielder seemed to get the memo. He wasn’t making a political statement or anything—he just had some weird ideas about how cool acting is, and wanted to share them with the world in an appropriately weird way. Of course it came off as alienating and distant to Richard Brody—the point was never to really understand the people involved—it was to understand the “rehearsal,” the Fielder Method, this one guy’s approach to acting.

It’s a bit self-obsessed, sure—but not nearly as inappropriately flattening as Borat or Am I Racist?. Fielder’s work is a purer kind of prankster comedy; a comedy qua comedy.

5. Wow, A Semi-Coherent Conclusion

Really, the prudence of the prank comes down to the intent of the prankster: if you’re trying to make a serious point or intelligently contribute to an ongoing debate, then Borat is not the movie to make. Emmanuel Levinas [as read by Jeffrey Murray, qtd. in (Lewis 2011)] is right: to understand and appreciate the Other, the Outgroup, takes “dialogic engagement.” You have to ask, “Did you mean to say…?”

Borat never asks for clarification, never probes deeper, never presents its subjects charitably. And that’s fine! It’s a work of comedy, and it works as comedy.

…But why should that make it a moral comedy?

Even if those objectified and caricatured are fundamentally to blame for showing the filmmaker their worst selves, there is a sort of spiritual cruelty to presenting them so unforgivingly. There’s something a little wrong-feeling about it, some sort of gross, unvirtuous vibe. Borat asks you to laugh at a bunch of people you don’t know, who’ve let their guards down and are treating a strange foreigner a little too chummily. Am I Racist? wants you to be amused when a bewigged Matt Walsh is allowed to interrupt and hijack a Race2Dinner session.

The joke, in each case, is that it takes a bit too long for the crowd to turn against the filmmaker’s character: Baron Cohen as Borat starts to lose a rodeo audience only after he’s expressed his wish for George Bush to “drink the blood of every single man, woman and child of Iraq”; Walsh eventually gets dirty looks and harsh words, but by then he’s already had everyone drink a toast “to racists.” It’s funny because the subjects are too lenient—they’re too charitable, in stark contrast to the comedian himself.

Isn’t that kind of icky? “Haha, you were too kind and permitting toward the stranger!”

The problem is, it works. Borat’s “We support your war of terror!” is one of my favorite lines from any movie ever; Matt Walsh’s excellent Robin DiAngelo reparations scene is only made possible by her admittedly-principled commitment to antiracism.

I think spiritual cruelty belongs in the same moral sphere as aesthetic enjoyment—to save shrimp from horrific suffering is more important than either; the two are competing for mere scraps of utility.

And in their battle, at least in the films I’ve mentioned, I’m pretty sure the aesthetics win—Borat is a really funny movie; about half the things my dad says on any given day are quotes from it. Am I Racist? was a very cathartic watch for me, and The Rehearsal hits a perfect balance of uncomfortable bizarreness and clever storytelling matched only, in recent years, by I Think You Should Leave with Tim Robinson.3

If these comedians are a little cruel in the process, well, so what? As Randolph Lewis admits (in line with Henri Bergson), “laughter must be cruel because it serves a cruel function: it is a social disciplinarian.” When we laugh, we do so in judgment: someone is the butt of the joke, someone is being lampooned, someone is being taken unseriously, being caricatured.

The deceit of the prankster is simply another method for determining a joke-butt—when it yields hilarious results, we should go ahead and laugh.

Not a “mockumentary.” Best in Show is a mockumentary: everyone’s an actor, and the comedy comes from people who know what’s going on. Borat is a very different kind of film.

An earlier, similarly-styled project of Baron Cohen’s.

I think Archer and It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, at their best, can reach this level too.

RE Snowden, not to condescend or anything, but you may not be old enough to have been aware of all the context…

Snowden was basically just acting out the post-Watergate whistleblower script without really having uncovered any major concrete harms. The NSA program he leaked on was basically just mass metadata gathering with an algorithmic analysis layered on top to determine suspicious patterns that might lead to probable cause for further investigation. It was never linked to any major systemic rights abuses or unjust prosecutions.

It was really just Snowden wanting to see himself as a hero like so many bad Xer freedom-fighting hacker movies from the 80’s and 90’s. Most of the public outcry was really stupid and just sustained itself on vibes and innuendo.