1. All Is Critical

Sometime in the 1970s, it became clear that the Civil Rights movement had not ushered in a new era of black American flourishing.

Cities like Detroit mostly saw violence, rioting, and white flight; condemned buildings littered their once-vibrant downtowns. Public schools were integrated in theory, but the worst-funded ones still taught mostly black students, and education achievement gaps stubbornly refused to close.

A veteran civil rights lawyer—now a law professor at Harvard—noticed all this, thought “hey, maybe pushing for totally colorblind integration wasn’t such a great idea,” and wrote a series of books and papers arguing as much.

His name was Derrick Bell, he wrote sane-sounding things like “effective schools for blacks must be a primary goal rather than a secondary result of integration,” and he’s often referred to as “the father of Critical Race Theory.”

Bell’s anti-integrationist philosophy was informed by a field just emerging in the US at the time—it was called “critical legal studies,” and its central claim was “that the wealthy and the powerful use the law as an instrument for oppression to maintain their place in hierarchy.”

In the next decades, critical studies would expand and multiply and become popular in countless more fields: Interested in disability rights? Check out critical disability theory! Gender’s more your speed? We’ve got a critical flavor of that too. Oh, you’re wondering how to teach all the different critical theories to your students? Why not try some critical pedagogy?

Of course, from academia, critical studies spread into all the other elite circles: DEI offices to keep everyone appraised of the latest in critical race theory, constant newsroom blowups over the fact that anyone—anyone—could possibly question the latest in transgender healthcare, and so on.

This was weird. Eventually people began to notice it was weird, and they started to scale it back a little, but not before it inflicted lasting damage to left-politics and academic elites. Trump’s election in 2024 was no doubt due to this strange academic obsession.

Now, I understand that I’ve pretty much missed the boat on this sort of “critical theory is stupid” take—today, the primary threat to academic and mundane freedoms absolutely comes from the right.

But I’m still writing this article, and I have a few reasons for doing so:

I want to be ultimately charitable to the now-mostly-reviled field of critical theory. I want to understand what their absolute best intention was, whether that intention had merit, and what value at all can be gleaned from it.

I want to know how this got so popular. Critical theory was a pretty marginal view back when Derrick Bell started writing about it in regard to race; it was just another species of continental-European Marxism. How did it get so huge in the States?

And, perhaps most importantly, how do we stop it from happening again? How can the left inoculate its thought-leaders and elites against the kookiest, most doomed and out-of-touch ideas they come across? How do we restore, and maintain, sanity?

2. What Is Critical?

Some months ago, I bought a very cheap used copy of a 1981 book called The Idea of a Critical Theory: Habermas and the Frankfurt School. It was written by a Cambridge philosopher named Raymond Geuss, and intended to summarize the fundamentals of Frankfurt School thought.

The Frankfurters were extremely prolific: their project was a synthesis of Marx and Freud; they wanted to understand how political philosophies as diverse as Stalinism and Nazism could’ve taken root in Europe, and to illuminate a better path.

There was no way I could ever take in their full corpus of work, so Geuss’ book was really a godsend—he distilled their system very simply:

The very heart of the critical theory of society is its criticism of ideology. Their ideology is what prevents the agents in the society from correctly perceiving their true situation and real interests; if they are to free themselves from social repression, the agents must rid themselves of ideological illusion.

It’s important to note that by “ideology,” the Frankfurters meant something very specific: it’s a pejorative term referring only to socially-held worldviews that cause “surplus repression.”

See, the Frankfurters weren’t idiots: they knew that running a society involved tradeoffs and suffering and unsatisfied desires. But an ideology can be leveraged by an elite class to shift more suffering than necessary onto some repressed group—more sneakily, the ideology can propagate itself and form a sort of social “consciousness.” It can convince the repressed class themselves that their repression is good, just, and necessary.

Importantly an ideological consciousness is adopted coercively: if placed in an ‘ideal speech situation’, with plenty of time and total free exchange of ideas, everyone would agree on some different consciousness (or “worldview” or “word-picture”)1 that satisfies everyone’s real interests somewhat better.

Consider, for instance, wartime patriotism: a social consciousness, enforced and coerced by the state, which says “it is good and desirable to die for your country.” Patriotism can convince many citizens to join up, or at least not revolt against the draft. But we say it’s an ideology in the sense that it works against its targets’ real interests: even if a young man desires to go off and fight in the war, given infinite wisdom and infinite time for deliberation, he would realize that he should instead desire to stay home and care for his wife and children. The patriotic ideology gets in his way: it convinces him that he wants something against his own interest; akin to a drug addict whose withdrawal symptoms convince him to desire narcotics, when his real interest lies in a desire to get clean.

The critical theorist’s first job, then, is to offer an Ideologiekritik.2 Some account of how the social consciousness is blinding citizens from their real interest (or, at the very least, convincing them not to pursue it), coupled with a believable description of what that real interest is, plus a vision for a new consciousness which allows that interest to be desired, pursued, and fulfilled.

Armed with an Ideologiekritik, the theorist then offers a whole big Critical Social Theory, composed of three parts:

A part which shows that a transition from the present state of society (the ‘initial state’ of the process of emancipation) to some proposed final state is ‘objectively’ or ‘theoretically’ possible.

…

A part which shows that the transition from the present state to the proposed final state is ‘practically necessary,’ i.e. that

the present state is one of reflectively unacceptable frustration, bondage, and illusion,

…

the proposed final state will be one which will lack the illusions and unnecessary coercion and frustration of the present state; the proposed final state will be one in which it will be easier for the agents to realize their true interests.

A part which asserts that the transition from the present state to the proposed final state can come about only if the agents adopt the critical theory as their ‘self-consciousness’ and act on it.

(Geuss p. 76)

The most striking thing about this description to me is that it’s sort of… boring. There’s nothing all that sexy about it: honestly, it reads more like self-help disguised as philosophy3 than a revolutionary project. There’s no violent overthrow, no seizing the means of production: just waking up, getting your shit together, and “realizing your true interests.”

Geuss doesn’t do much editorializing—it’s a short book, less than 100 pages—and so his summary left me still wondering:

Why did this catch on?

Why did it fail so spectacularly?

3. Why Did Critical Theory Catch On?

The devil is really in the details here. Critical theory is a sneaky sort of radicalism; less garish than the Marxist-Lenninists and black nationalist movements that preceded it; much more acceptable in the post-Vietnam era of total neoconservative and neoliberal dominance.

As far as I can tell, the key features of critical theory which made it such an addictive meme were:

Blaming Ideas

We’ve got to remember that all this went down in the academy, among humanities and social science professors who’d never done an honest day’s work in their lives. To them, “praxis” probably wouldn’t mean labor-organizing at the coal mines: it would mean court cases, amicus briefs, stinging op-eds, and books.

The question isn’t “which radical meme is the sexiest?” It’s “which radical meme is the sexiest to a bunch of wordcels and strivers who’re jostling with each other for status and acclaim?”

The best kind of radical theory, then, lends itself well to the pages of an academic journal—and critical theory, which is entirely about blaming big ideas (“ideologies”) for social ills, fits perfectly.

Instead of ranting and raving about billionaires and capitalists, academics could rant and rave about one another. They—society’s tastemakers, society’s bureaucrat- and journalist-teachers—were ultimately responsible for all the ideologies which suppressed the common man.

And so it was a bloodbath among vampires: professors starting fights for clout, exiling their fellows over insufficient critical-ness, and spinning up endless epicycles about the proper, non-ideological, liberatory ways to do academics.

Critical theory told this particular group of obsessive literate narcissists that their obsessions and their writings were the absolute most important thing. So of course they loved it!

Paternalism and Unfalsifiability

Quite frankly, the definition of real interest offered by the Frankfurters is painfully broad. They seem to believe that ideology suppresses agents’ pursuit of their interest in a number of different ways, and that the visibility of the effects range broadly. Sure, sometimes a man will know exactly what’s in his best interest, he’ll realize he’s not getting it, you’ll point out in your Ideologiekritik how society is stopping him, and he’ll be radicalized.

But the formation of critical social theory can also look a lot more subtle than that—Geuss summarizes “four quite different ‘initial states’” that theorists are looking to emancipate us from:

agents are suffering and know what social institution or arrangement is the cause;

agents know that they are suffering, but either don’t know what the cause is or have a false theory about the cause;

agents are apparently content, but analysis of their behavior shows them to be suffering from hidden frustration of which they are not aware;

agents are actually content, but only because they have been prevented from developing certain desires which in the ‘normal’ course of things they would have developed, and which cannot be satisfied within the framework of the present social order.

(Geuss p. 83)

Surely the issues with (3) and (4) are clear!

Suppose a critical theorist sees a man on the street shining shoes. He might go up to the man and say, “You have a false consciousness arising from an ideology which tells poor men like you that they must be employed in undignified, embarrassing, servile work like this.”

If the man replies, “No I’m actually pretty happy being a shoe-shiner,” then the academic can say, “See?? Look how deeply false your consciousness is!! you don’t even know how to want to live the Good life!”

This makes it really hard to disprove anything a critical theorist says! Memes that insist on themselves unfalsifiably like this are really hard to kill: consider, for example, religion.

“God knows best, and if something bad happens, that was simply God’s will, his motives remain unknown, it’ll obviously work out in the end, what, you don’t believe me, are you saying you don’t believe in God, how can you not believe in God when everyone around you does, really only a totally morally bankrupt person would deny God’s existence, look at all that God’s hand has created and be thankful!”

Quite similarly: “Oh, so now structural racism doesn’t exist just because my central claim about police shooting mostly unarmed black people is wrong? No, all that proves is that the structural racism is even more insidious and hard to detect—and, by the way, you’re obviously complicit in it for trying to deny that fact, you’ve clearly got the false consciousness, and we need to critical-theoricize it out of you.”

Ideologies are all-pervasive: contravening evidence is just another layer of conspiracy!

I’m Just Asking Questions, but You’re Obviously a Dumbass if You Answer Anything but “Yes”

Marxism’s great embarrassment was how unbelievably wrong all of its predictions were. Marx thought that the proletariats of the wealthy Western industrialized states would all rise up and revolt, and that turned out to be super wrong in sixteen different directions.

The Frankfurt School, on the other hand, never made any claims about inevitability: it took the (very passive-aggressive) stance that it would simply be “rational” for everyone to rise up and do the revolution/reckoning in question.

The members of the Frankfurt school take it as an important distinguishing feature of their ‘critical’ version of Marxism (and a sign of its superiority over more orthodox versions) that they do not categorically predict the ‘inevitable’ coming of the classless society. Marxism as a theory of society claims to give knowledge of the necessity of a transformation of the present social order … [In contrast,] the real point of the critical theory is not to make categorical predictions, but to enlighten agents about how they ought rationally to act to realize their own best interests.

(Geuss p. 77)

This made critical theory a much less risky endeavor than full-bore traditional Marxism. Anyone who wanted to seem good, smart, and radical could jump right on board: if they turned out to be wrong, and the revolution/reckoning never actually came, they could simply say, “But I never said it would happen, just that if you all were as smart as I am, maybe we could’ve done it. Oh well!”

Not only does this property make critical theory an attractive meme, it makes it sticky too.

has written an excellent article called The Resistance Is Gonna Be Woke. He thinks no one’s really learned their lesson, and that by 2028, AOC’ll be on the campaign trail spouting the same old talking points from the same old critical theories.After reading Geuss’ book, I’ve come to think it’s a lot more likely he’s right.

4. Why Did Critical Theory Blow Up in Everyone’s Faces?

Oops, it’s all the same reasons it got so popular!

Successful Revolutions and Emancipations Involve the Doing of Actual Stuff

It’s certainly very fun to start beefs for clout and masturbate up in the ivory tower, but if you want real social change to happen, you’ll need to engage in all the boring old meatspace activities too: you need to seize the means of production, you need to (possibly violently) wrest control away from one regime and give it to another.

I’m not saying it would be good if the critical theorists tried to do this: just that the philosophy’s hands-off, just-change-the-social-vibes approach was doomed from the start.4

The People You’re Emancipating Need to Want to be Emancipated

As fun as it is to scream crazy unfalsifiable things at passers-by while you protest on the quad, it probably won’t do you much good if the things you’re saying aren’t relatable to anyone.

For instance, the vast majority of Americans (and about half of black people) think that structural racism is way less salient than people-being-jerks. Critical theory deals mostly in laws and the ideologies behind them, and less in interpersonal tribalistic animus.

Certainly you could devise a critical theory aimed at interpersonal racism, but you’d need to find some version of it that’s acceptable to the elite, and that you could call “ideology.” I think that the difficulty in finding something like this was what led to “microaggressions,” one of the silliest overextensionsof critical theory. Remember, the point is to convince the suppressed class that they’re experiencing some sort of real harm—and you’re gonna have a hard time telling people that asking “where are you from?” is an act of violence.

When we look at successful emancipations and revolutions, we find more genuine and obvious immiseration: slaves really truly disliked slavery; serfs really truly disliked serfdom.

No One Likes an Out-of-Touch Know-It-All

This is the big #1 reason. Intellectual elites became totally-convinced of their moral clarity, started doing wacky things with apparent impunity, and there was a harsh reaction. If you’re gonna do a political movement, you have to stay humble and man-of-the-people-ish, or else Chris Rufo will come and eat your babies.

5. Critical Theory Is an Ideology

I have to admit, I’ve got a bit of a soft spot for the Frankfurters’ account of ideology and ‘real interest’. As much as it’s paternalistic and self-absorbed, it’s also interesting and true-looking.

Our social religions are really important to the way we think—hell, our regular religions are too. The platonic liberal ideal that says no one is ever deluded or coerced or otherwise stopped from perceiving their interests is obviously wrong.

And what the Frankfurt School has done an excellent job of is reasoning about how this happens and what effect it has on the psyche.

Which brings me to a sort of strange claim: I think the woke mindvirus has a lab-leak origin.

The fact that an academic movement derived from the fight against desire-strangling ideologies so quickly became a desire-strangling ideology itself is impossible to ignore.

Sure, part of this is just how social movements always work: everyone goes too far and gets too illiberal from time to time. But, I mean, come on!

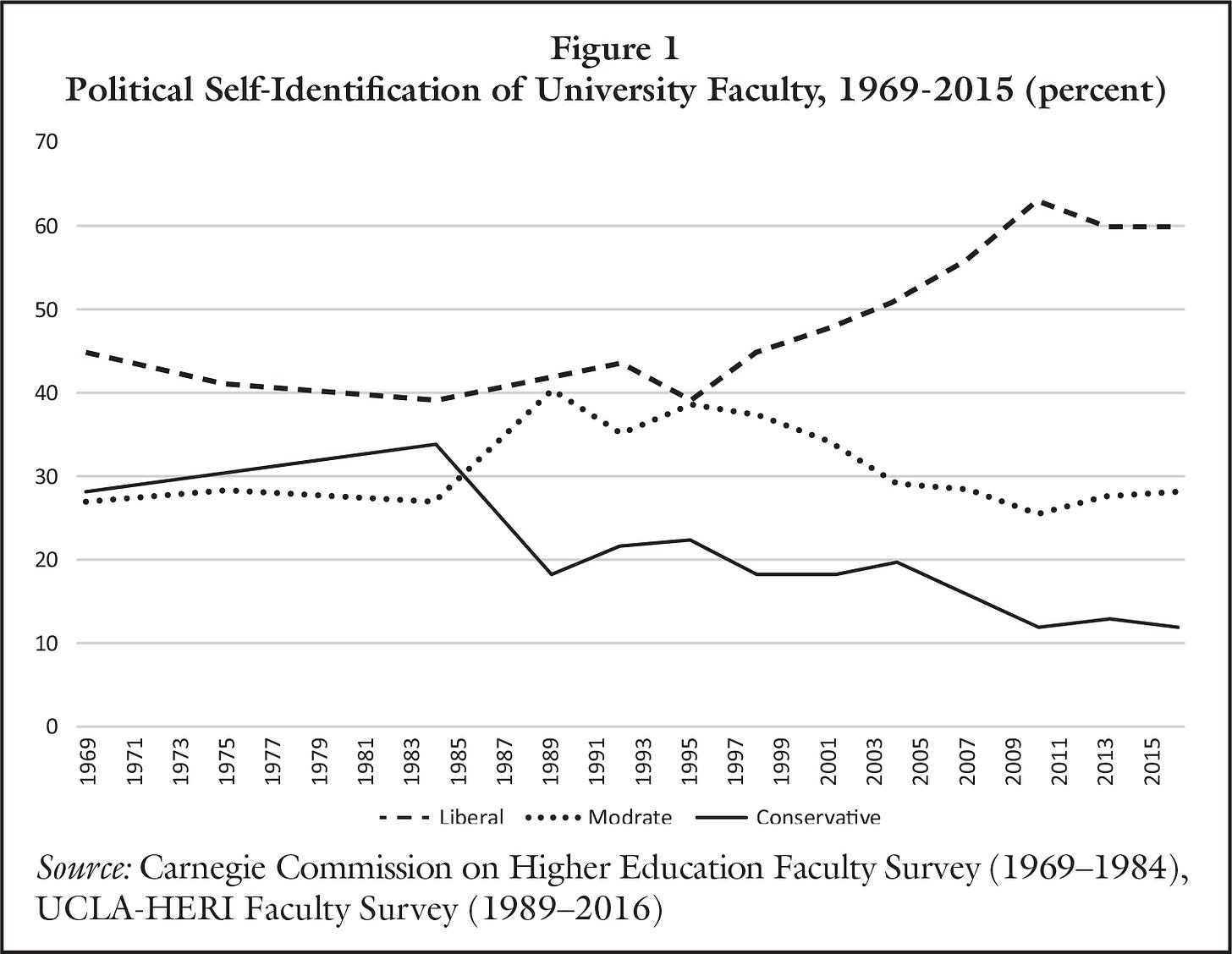

Obviously the critical theorists were exceptionally good at creating a monoculture in their fields—academia’s always been pretty left-ish, but in the 80s and 90s—as critical theorists wiggled onto hiring committees and into department chairships—it got really left-ish:

And it’s not like the American critical theorists popped out of nowhere! In the 60s and 70s, Frankfurter Herbert Marcuse and his American student Rudi Dutschke developed a strategy they called “the long march through the institutions.” Marcuse described it as:

[W]orking against the established institutions while working within them, but not simply by 'boring from within', rather by 'doing the job', learning (how to program and read computers, how to teach at all levels of education, how to use the mass media, how to organize production, how to recognize and eschew planned obsolescence, how to design, et cetera), and at the same time preserving one's own consciousness in working with others.

The long march includes the concerted effort to build up counterinstitutions. They have long been an aim of the movement, but the lack of funds was greatly responsible for their weakness and their inferior quality. They must be made competitive. This is especially important for the development of radical, "free" media. The fact that the radical Left has no equal access to the great chains of information and indoctrination is largely responsible for its isolation.

And it… worked!5

These experts-in-ideological-suppression marched through the institutions, took them over, and then instituted a regime of near-McCarthyist-level suppression!6

How do you stop this from happening again?

Make the institutions more rigid! If you lock in values like neutrality, transparency, and due process now, then it becomes a) much harder for an illiberal radical to make it to the highest levels of administration without sticking out like a sore thumb, and b) much harder to install a fear-based regime. Professors should answer to truth, not the university president. And politicians should answer to voters, not the Groups.

If you believe in those principles, you’ve gotta lock them in. You’ve gotta reform the governance structures and strengthen tenure and do all the little boring, unnecessary-feeling things now.

6. Conclusion Time

What if there was another way?

Instead of fighting critical theory—impressively infectious meme that it is—what if we could reform it slightly, reconceive it in a less-insane format, and quit all the fighting?

Geuss closes his book:

Not all empirical social inquiry must have the structure of critical theory, but the construction of an empirically informed critical theory of society might be a legitimate and rational human aspiration.

That seems about right to me.

Raymond Geuss knows German, so I think it makes sense to him to translate one German word in three or four different ways, because the original meaning is something in between each of the translations. That’s cool for him and all; for me it’s just really frustrating and confusing.

If you clicked this footnote looking for a translation, you are officially dumb.

Would fit right in on the Substack leaderboard…

Quick note here to say: something something Gramsci, yes you also probably need to put in some effort to change the social vibes.

…Sort of: Marcuse was less critical theorist and more New Leftist. His version of radicalism was explicitly socialist—not vaguely culturally progressive. He probably didn’t get the long march he wanted, but his idea was very fundamentally Frankfurtian: if emancipation is an intellectual and non-inevitable task, then you’ve got to take intentional action to secure the bastions of the intellectual elite in order to get anything done.

I think it was more impressive when the critical theorists did it, because they didn’t have the force of law behind them: cancellation was their only weapon, and yet they instituted a remarkably effective reign of terror.

![The Idea of a Critical Theory: Habermas and the Frankfurt School [Book] The Idea of a Critical Theory: Habermas and the Frankfurt School [Book]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!odnd!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F3f81a538-9e39-4b1b-b347-b00457ed571b_880x1360.jpeg)

"This is the big #1 reason. Intellectual elites became totally-convinced of their moral clarity, started doing wacky things with apparent impunity, and there was a harsh reaction. If you’re gonna do a political movement, you have to stay humble and man-of-the-people-ish, or else Chris Rufo will come and eat your babies."

Most successful revolutions are led by out of touch vanguards. Including the much vaunted Civil Rights.

"Instead of fighting critical theory—impressively infectious meme that it is—what if we could reform it slightly, reconceive it in a less-insane format, and quit all the fighting?"

This is not a good idea, because it relies on the assumption that a person has understandable interests separate from ideology. This is a mistake. Patriotism is assumed to be bad because a man should never want to risk his life, even though he can benefit from winning this gamble.

Huh, I am a Euro, and that is not how I learned about this... basically it started with Kant's critique of pure and practical reason, that there is a gap separating how things are and how we perceive them. Then Marx figured that the reason we do not perceive things as they are, are oppressive social stuctures. This had set up Frankfuters but also others like Bordieau and Foucault. The central idea was that when we perceive something as good, as opposed to bad, such as "good taste", it is the viewpoint of the power elites.