1. The Gentrification of Everything

There’s a lot of injustice in the world. Bad things happening to good people; it’s all over the place.

Sometimes, this injustice is even perpetuated systemically. All that means, really, is that social supports don’t go far enough to alleviate it. We say that we care about the lowliest, unhealthiest, most unlucky among us—but when push comes to shove, the wheelchair ramp would cost an extra few thousand bucks, and sorry, there’s no room in the budget.

If this keeps happening and happening, and you build the library and the courthouse and the school all without wheelchair ramps, someone in a wheelchair might begin to wonder what the fuck is up. If you’re talking a big game about a robust safety net, why can’t you do even the bare minimum to accommodate them?

So they lobby and they instigate until you pass an Act for Americans like them with Disabilities. And, under the provisions of the Act, you have to install ramps outside the library and the courthouse and the school, and all the wheelchair users seem happy and fine.

…But you start feeling kind of left out. Of course, disability extends well beyond the physical, doesn’t it? You’ve always had kind of a hard time focusing on any one thing for a while; your attention drifts and you don’t get quite as much work done as the guy in the cubicle next to yours.

That’s sort of unfair, you think. After all, if it’s wrong for a wheelchair user to be disadvantaged by stairs, which make it harder for them to compete with you, then isn’t it wrong for you to be disadvantaged by distractions? Don’t you have some kind of right to an accommodation? Something that levels the playing field?

Maybe you should join that old, mostly-defunct disability rights group. You can help bring it back to life; give all the old activists something new to advocate for.

Once you do bring it back to life, and advertise it around the office, you’re surprised to see how many of your coworkers join. Some of them are socially awkward, or anxious, or have trouble paying attention, just like you. Many have diagnoses for ADHD and GAD and even autism or Asperger’s.

The group’s Old Guard has a few people like this too—with some sort of mental illness diagnosis—although you notice they tend to be a lot less successful than you and your buddies. Many are poor or homeless, few are… photogenic, to say the least.

So when you do your press conferences and take pictures for your PR campaigns, you tend to shunt those people off to the side. And you put the pretty and successful autists in front of the microphones; schedule interviews for the ADHD-sufferers who could buy enough Adderall to last four years at Princeton.

Naturally, more of these kinds of people join your movement, and so your movement starts to cater mostly to what they want. The schizophrenics and paraplegics are forgotten; disability activism is really about ego-stroking for your white collar friends.

And so disability activism should be about awareness-raising and silly little upper-class things like extra test-taking time in college, and more representation on TV, and so on.

***

Freddie deBoer has called this The Gentrification of Disability. The process by which an activist program targeting a very specific, very obvious injustice was hijacked by one set of elites to gain privileges and status over another set. Left behind were all the seriously disabled people whom the program was initially meant to help.

extends the concept to the Great Awokening in general.1 He writes about how a generally good-faith attempt to reform society for the better—to reduce police violence, say—was disembowled by a class of “symbolic capitalists”2 who used its language to play stupid status games and fix nothing. It was never about Black Lives Mattering—it was about stripping tenure from anyone who didn’t put a black square in their Twitter bio.I think there’s a sense in which he’s too charitable—it’s far from clear that even the best-intentioned BLM protesters would’ve accomplished good things had they been empowered—but he’s right that they largely weren’t empowered. Concerns about racism were laundered and gentrified and turned into a totally-disconnected elite status game. Any black people who really were still suffering from racism and its consequences—suffering from rampant poverty and crime and an inability to build up wealth—were utterly ignored.

My sense is that this phenomenon generalizes well outside of social justice-y things. Pretty much any noble-ish cause that’s adopted by the elite class will end up distorted, meaningless, and ultimately doing more harm than good.

2. They’re Coming For Exploitation

Or, more precisely, they already have…

Exploitation refers to a bad thing. It’s a value-laden term, it implies that something unjust is happening and we have a responsibility to take action. Classic examples of exploitative labor are things like:

Slavery: you can pay a slave much less than they’re worth, because if they try to complain, then the state will do terrible violence to them.

Migrant workers: you can pay an illegal immigrant much less than they’re worth, because if they try to complain, then the state will do terrible violence to them.

Human trafficking: you can force a young runaway to have lots of sex with lots of people, because if they try to complain, they’ll have no money, no prospects, and no home to get back to.

These are obviously-awful situations. There’s a lot of harm being done to those exploited, and there are obvious and cheap levers that the state can pull to make them better. The state can say, “Oh, actually, we’re not gonna hunt down fugitive slaves. Better yet, we’ll hunt you down if you try to force someone to work under threat of violence!”

Or the state can say, “As long as someone isn’t committing felonies and is paying their taxes, we’re not gonna raid the Home Depot parking lot to send them to a torture-chamber in El Salvador.”

And they can say, “If you do sex-trafficking, we will send you to a torture-chamber in El Salvador.”

It’s very good to advocate on behalf of exploited people. It’s important for the mechanisms and systems of violence that exploit them to be dismantled; it’s important to shift the incentives and to target the exploiters instead.

But you know what really isn’t very good at all? To totally dilute the concept of “exploitation.” To say that everyone everywhere all the time is being exploited because the firm they work for is making a profit.

Because if you did that, then the symbolic capitalists could swoop in and claim they’re being exploited at every turn. They could use it as a wedge in their endless lingual circlejerk, and all of a sudden, the really exploited people who need our help would be hung out to dry.

So, really, let’s try to avoid tha—

Fuck.

3. Karl Marx Is Not My Kind of Guy

It really always is his fault.

Chris Rufo is a big fat stinking idiot in so many ways, but he’s right about Cultural Marxism. “Critical Race Theory” was a type of “critical theory”—Marx really was the father of critical theories.

The point of the critical theories is to explain how every little-injustice is connected to some kind of big-injustice that actually impacts everyone. It’s a good political strategy! It’s big-tent-ish: Marx isn’t saying that everyone should give charity to the downtrodden few—he’s saying that the Systems Of Injustice are trodding-down on everyone. It’s fundamentally an appeal to self-interest.

If anything, the problem is that it was too successful an appeal. If you propose that the world is full of shadowy forces, each one targeting a vast swath of the population, then basically everyone will think that they’re going up against a shadowy force—even the symbolic capitalist elites.

And since all the different shadowy forces are ultimately indifferentiable, the symbolic capitalists will happily adopt the language of the truly-downtrodden, claim they’re on the same side, and then begin to play their status games. The symbolic capitalists control the presses and the universities and the levers of government—and so they’ll do their damnedest to totally ignore injustice once they’ve performatively condemned it.

Because it’s not just the trafficked-sex-workers who are being exploited and must be protected by state-power—it’s also voluntary-sex-workers! Nevermind that whole “bodily autonomy” thing—it’s much more important to win virtue points by whinging over how oppressed and commodified and exploited the woman’s body is!

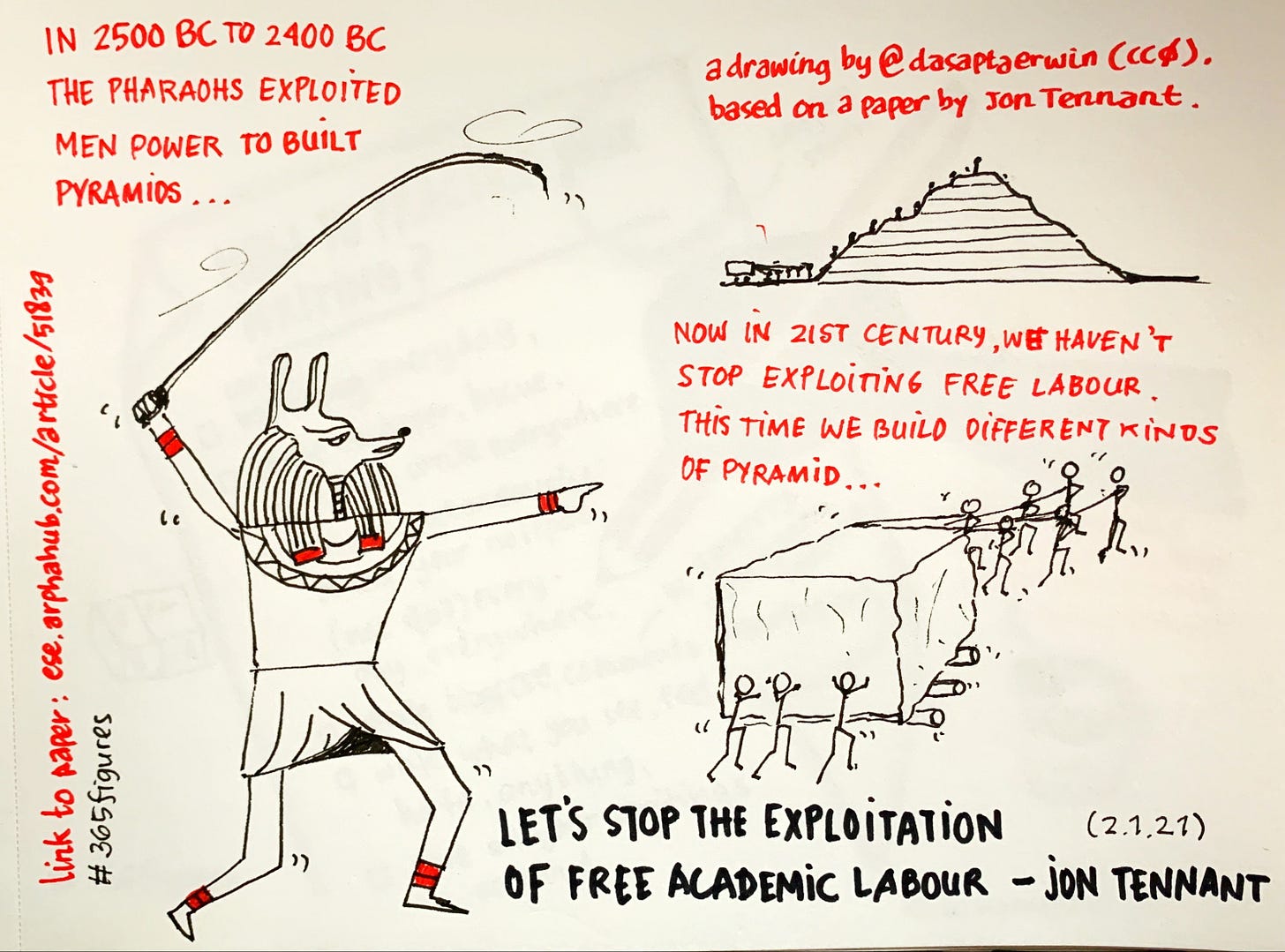

Perhaps the worst perversion of “exploitation” was best described by

; it’s got to do with payment for organ donors:There is no good excuse for this. I bring it up because I was listening to the most recent episode of

, an interview with radical feminist Julie Bindel. I thought she sounded smart, quick, friendly, and totally incredibly wrong about this. At one point, in order to make some analogical argument about how medical autonomy is Bad, Actually, she asks host Katie Herzog:What should we do with those people who remove a kidney from a person who wants to sell it because he or she are so desperately poor that they really need this to put a roof over their heads, or the heads of their children? Should there be any sanctions on that surgeon?

Herzog (correctly) replies that, obviously, no, there should not be any sanctions on that surgeon!

“I’ve seen it as a response to dire poverty,” replies Bindel. And then she goes on to diss both surrogacy (surrogacy!) and prostitution for “turning the body into a workplace.”

This is totally crazy. This is exploitation gentrified—if a woman (or anyone!) chooses to use her body to make money, not as a result of violent coercion at all, then please point me to what exactly has gone wrong. Where’s the exploitation?

If the only thing compelling her to make that decision is her poverty, then you’re gonna have to tell me that the existence of poverty is inherently exploitative.

In which case, I will ask you: if I take a crappy job at McDonald’s because I’m poor and I need the money, have I still been inappropriately exploited? Or what if I take a job that you think is demeaning, but I actually happen to kind of like? Am I still being exploited?

Bindel’s argument is rooted in the Marxist notion that exploitation is everywhere. And when you think exploitation is everywhere, it becomes a lot harder to find and deal with the little-exploitations that cause real harm. The slave-laborers that make Nike shoes; the women who are being forced into sex work against their will.

These are morally different situations—don’t trade the dichromatic Black-and-White for a monochromatic Gray. There’s exploitation and there’s “exploitation”: if a woman who chooses to sell her kidney—saving a life and making some money in the process—is being “exploited,” then the word’s totally lost touch with the value-judgment it’s meant to convey.

“Exploitation” has become totally gentrified—for the sake of organ recipients, immigrant workers, and all the other unlucky schmucks who’ve been evicted, I hope we can claw back some ground.

I think deBoer’s How Elites Ate the Social Justice Movement makes a broadly similar point, but I haven’t read any of it, whereas I’ve read like half of al-Gharbi’s book, so I’m gonna use the language he uses.

Aka “the professional-managerial class” aka “wordcels.”

Elites will end up appropriating everything.

More depressingly, even if elites fail to appropriate a movement, the success of that movement will create a new elite.

This is going to be a thing as long as humans are ambitious.

The (Straussian?) response to the claims of Marx ruining everything is that any sort of wedge issue that could create a High-Low coalition vs the Middle is going to very quickly turn into elite status games. Seems to be an incurable feature of bourgeois societies.