1. Contrarianism Is Radicalism

claims to be a “woke conservative.”He’s woke because he cares about injustice—particularly the hugely-neglected kinds, like factory farming, shrimp eyestalk ablation, and insect suffering.

And he’s conservative because he’s “quite moved by the traditional Burkean arguments that good things are hard to create and easy to destroy … if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

To be fair, Bentham’s only talking about preserving political institutions there. But conservatism is a somewhat broader mindset—I’d argue that a truly consistent version is less of an approach to politics than one to society at large. And so the conservative instinct tells us that both our political and social institutions fall into this category—the set of things that we should initially assume are good, and that are probably much easier to destroy than create.

Now, Bentham also believes that it’s more virtuous to hold unpopular moral views than popular ones. There’s a special goodness to campaigning for what you believe in if you expect to face social costs:

You get a lot more virtue points for promoting gay rights when your friends all oppose gay rights than when your friends support gay rights. You get a lot more virtue points if you do the right thing but don’t get credit for doing it—if you’re willing to risk seeming like a weirdo for the sake of doing the right thing.

I think this idea is obviously opposed to conservatism. If weird views are better than non-weird ones, we should be spending most of our time destroying various social institutions. After all, to be institutionalized, something must be fairly popular, fairly mainstream—to fight institutions, then, is weird and worth lots of virtue points.

This isn’t necessarily unreasonable—Bentham does stipulate that you only get the virtue points if you’re “doing the right thing.”

But it is necessarily at-odds with conservative instincts. No (serious) progressive has ever advocated destroying institutions just for the hell of it—they too think that it’s worthwhile for the sake of “doing the right thing.” The only difference is that, for them, the right thing to do is more likely to be a struggle session or cancellation, rather than a donation to the Shrimp Welfare Project. Bentham’s cause may be different, but his approach is the same: he’s a radical, not a conservative.

2. But Shouldn’t We Be Radicals? Isn’t It More Interesting?

shares Bentham’s view that contrarianism is a virtue. He writes, defending :I am an exponent of the peculiar belief that it is generally better to be smart and interesting than it is to be dumb and boring.

I know this is a peculiar belief because most of the smartest and most interesting people in the world are also the most controversial and despised.

…

It is virtuous to believe in shrimp welfare when nobody cares about shrimp. It is similarly virtuous to believe, as I do, that dream welfare matters, that we ought to spend a lot of money on fish contraception, and that we have good pro tanto reasons not to clean up the Hudson River.

It is even sometimes virtuous to believe — as opposed to “act on” — widely discredited and historically destructive ideas and ideologies, including Marxism-Leninism, racial supremacism, and the belief that Amos Wollen and even Ari Shtein are anything but Very Failed Substackers — so long as you believe these things as part of an earnest and good-faith truth-seeking enterprise, and you would be dissuaded out of your beliefs by the proper evidence.

Glenn is willing to bite nearly all the bullets this view entails. Even if you think that I—supporter of Ukraine and opponent of Nazis1—am somehow not Very Failed, you still get virtue points, just so long as you don’t do anything crazy like click this big beautiful blue button:

I’m not really sure that Glenn’s belief / action distinction helps him out much. People who hold radically non-mainstream views tend not to sit around twiddling their thumbs—they’re much more likely to assassinate healthcare CEOs or donate to shrimp charities. And the ones that do sit around twiddling are pretty obviously not virtuous people. We make fun of them!

And so we’re forced to deal pretty directly with the radical implications of valorizing contrarianism. What are those implications?

Well, I wonder who Glenn’s counting among the “smartest and most interesting people in the world.” Surely, great moralists like Peter Singer and Will MacAskill are up there; they’re well-despised enough. Someone like Jesus, on the other hand? Ugh, so loved, he’s not interesting at all.

Maybe we can include some smart and interesting philanthropists too: Bill Gates? Well, he has his haters, but people generally seem to like him. Not so virtuous, Bill! What about George Soros? Sure, he’s really despised by some, but his net favorability breaks even. Ah, I know: Sam Bankman-Fried! He had the right ends in mind—he was donating to animal welfare and global development and longtermism—and he was obviously smart too. Best of all, everybody hates him, and he even tainted the social movement he was a part of, helping us all to be a little more hated and a little more virtuous! What a mensch, that SBF.

If Glenn’s willing to compromise on his view that it’s virtuous to believe in “widely discredited and historically destructive ideas and ideologies”—given that it’s a) likely that such a person would act on their beliefs and b) super lame and unvirtuous if they don’t—then the obvious objection is simply that SBF was wrong. Contrarianism only counts as a virtue if you’re right, and if you don’t do obviously wrong things like stealing all your customers’ money.

…Which just puts us back in the same spot as before. Radicalism is good if you’re right and bad if you’re wrong.

3. You Don’t Know That You’re Right!

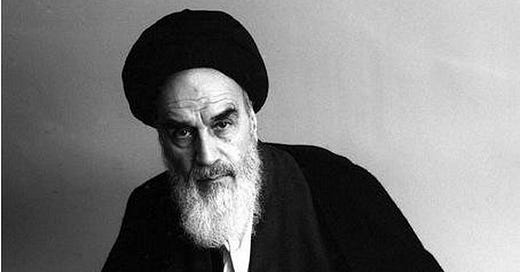

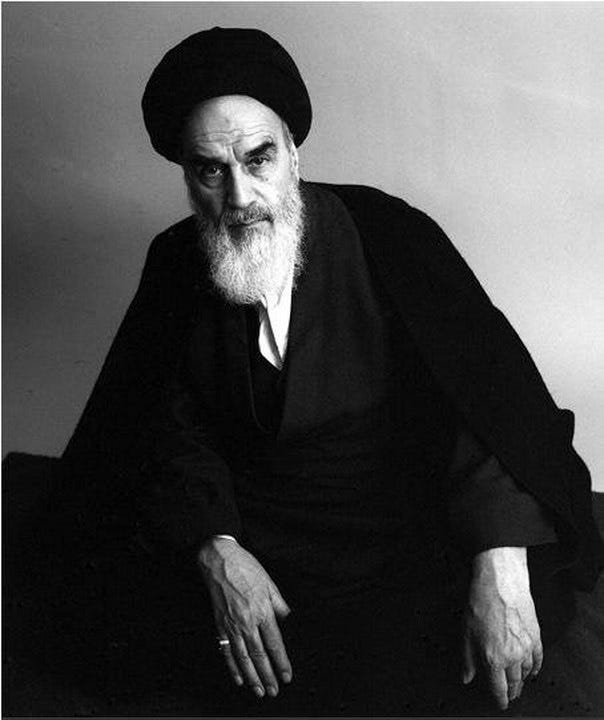

Every radical anywhere ever has thought they knew what the worst thing in the world was, and what the best solution would be. Kendi thinks the worst thing is racism and the best solution is discriminating against whites. Lenin thought the worst thing was the Tzar, the second-worst thing was liberal democracy, and the best solution to both was Bolshevism. Khomeini thought the worst thing was the Pahlavi dynasty and the best solution radical Islamist terribleness. Rinse and repeat, over and over, everyone ever.

Yes, I know, we have better evidence for effective altruist causes than anything before. We have great and thoughtful philosophers (and Substackers), we have randomized controlled trials, we have a rationalist and cautious culture. SBF was a fluke! SBF was a dramatic event—we can’t over-update on those!

Effective altruists have saved 200,000 lives! We have a good record! Our critics are largely uncharitable morons!

I’m not making fun—I really believe all these things too. I’m just worried that, were I a committed antiracist or Bolshevik or Khomeinist, I would be thinking along frightfully similar lines. I need second-order humility—I need to hedge against the chance, however slim it may feel, that my priors are hopelessly trapped.

Scott Alexander admits that sometimes we should learn from dramatic events!

[A] dramatic event can reveal a deeper flaw in your models. For example, suppose there is an enormous terrorist attack, you investigated, and you found that it was organized by the Illuminati, who as of last month switched from their usual MO of manipulating financial markets to a new MO of coordinating terrorist attacks. You should expect new terrorist attacks more often from now on, since your previous models didn’t factor in the new Illuminati policy.

If I thought effective altruism was a collection of mild-mannered and intellectually humble people saving hundreds of thousands of lives, and then EAs started stealing millions of dollars, and then proclaiming a new utterly overwhelming moral priority every couple of weeks, and then boxing alt-right morons (for charity!), I might begin to doubt the mildness and humility of the movement!

I think Bentham’s Bulldog is a great philosopher, great writer, and all-around good person—but it seems like he’s beginning to drift too far into outrageousness and contrarianism and catastrophizing. It’s not virtuous—it’s frightening and unpleasant and unconvincing.

4. Crap, I Need a Conclusion

I’ve lost the thread a bit, haven’t I? That word—catastrophizing—I’ll have more to say about it soon.

But for now, let’s stick to contrarianism and how it isn’t necessarily virtuous. How it’s the being right that’s worthwhile, not the being unpopular. And how being unpopular tends to count as evidence against being right—that’s the conservative instinct.

Glenn might object to that instinct—recently, he commented:

If you think most beings who are deserving of moral patienthood are systematically excluded from the moral circle, and we’re committing countless ongoing moral catastrophes because of this, it seems that the default position toward Our Norms and Institutions should be enlightened radicalism, i.e., that most of them ought to be torn down as soon as practicable, and the only reason for conservatism is that we first have to figure out what to replace them with.

Again, we need some second-order thought here. Every radical ever has thought himself “enlightened.” Every single one has thought that there are countless ongoing moral catastrophes, and that the Norms and Institutions must somehow be responsible.

I think that even if you’re really confident you’re right—even after you’ve taken the outside view, asked if you’re just one more run-of-the-mill radicalist in one more radicalist cult, and answered that you’re not—you should favor protecting Norms and Institutions over tearing them down.

Because the truth is that the “figuring out what to replace them with” is an incredibly lengthy and difficult process. Scott Alexander wrote, decades ago in early February, that Money Saved By Canceling Programs Does Not Immediately Flow To The Best Possible Alternative. That’s just one consequence of the broader principle that the world is super complicated—institutions end up doing lots of things (many of which aren’t their purpose!) and it’s difficult to know what, exactly, you’re tearing down, much less whether you ought to be.

Contrarianism-as-virtue fails on an even deeper level, though. It’s vulnerable to

’s cheesecaketarian reductio. If maximizing shrimp welfare is especially virtuous because it’s unpopular and we don’t feel an emotional connection to shrimp, then maximizing the amount of cheesecake in the universe is even more virtuous, given that it’s much less popular and we feel even less of an emotional pull to do so.Again, the objection will be along the lines of “shrimp welfare is more likely to be a ‘right’ thing than cheesecake-maxxing.” Fine, fair enough, let’s construct a more general example then. I have three premises:

Beliefs earn virtue points based on their rightness and on their weirdness.

Beliefs can only earn weirdness virtue points if they’re right. Of course, since we can never be 100% certain of rightness, we either need some credence threshold—which is bound to be arbitrary—or we should view this whole thing from an expected-virtue lens. A belief in which I have 90% credence gets 90% of the credit for its weirdness, and one in which I have 10% gets 10% of the credit.

It’s possible to add clauses to a belief that makes it weirder without making it significantly less likely to be true, and this is the case to an arbitrary extent.

Then we can deduce:

Given a belief B with weirdness W in which I have rightness-credence C, the expected virtue (EV) of holding this belief is some quantity V.

By (3), we can imagine a belief B’ with weirdness W’ > W and rightness-credence C’ < C where W’ - W > C - C’.

By (1) and (2), anyone who holds belief B’ will end up with EV = V’ > V.

By (3), we can arbitrarily induct on the proposition that V(k+1) > V(k) and will eventually reach a belief B(n) with C(n) arbitrarily small such that V(n) > V.

Premise (3) is probably the most contentious. I think it holds—you can add weird crazy clauses that have little bearing on truth, but certainly amp up the weirdness. For instance, maybe you believe that shrimp welfare is important—pretty right and pretty weird! But what if I believe not only that shrimp welfare is important, but also that the welfare of this one Indonesian shrimp I know named Ishmael is a little extra important. Seemingly, my belief is still very right—I care about all the shrimp a lot and will probably donate just as much to the Shrimp Welfare Project as you—but it’s obviously much weirder and much less popular. Very few people care about shrimp, but even fewer care about Ishmael! How virtuous am I, sticking up for the unspoken for.

5. Oops, Still Need a Conclusion

You don’t necessarily have to accept my argument about the intrinsic virtue of weirdness, though I think you should. It’s still true that prioritizing contrarianism is radical and overbearing. Most contrarians throughout history have been wrong and it’s shockingly hard to alter institutions—political and social—to fit your ends.

You should save the shrimp because shrimp suffering matters—not because it’s edgy to say shrimp suffering matters.

In all honesty, I’m beginning to seriously reconsider my view on blowing the Houthis to bits. Glenn,

, and all made great conceptual counterarguments in the comments. Also, despite all the blowing-to-bits we’ve been trying to do recently, very few Houthis seem to actually have been blown to bits. Both theoretically and practically, I’m starting to look a bit out over my skis.

Really my main issue with contrarianism is that increasingly narrow social circles mean it's really hard to tell what is actually contrarian. The idea behind contrarianism being virtuous is that it proves you're willing to incur social costs to defend truth, but if you say "I support shrimp welfare" and all your friends are Effective Altruists, you aren't incurring any social costs. If anything, the contrarian view that incurs social costs for you would be to go around telling people you hate shrimp and want the nasty little bugs to suffer. Then all your friends will hate you and think you're weird.

I think a lot of people think of themselves as brave contrarians when really they're just parroting the views their social circle agrees with and basking in the applause. This is why annoying people on reddit say things like "unpopular opinion, but I think Trump is bad" and get 3000 upvotes for being a brave contrarian. After all, Trump won the popular vote, so anyone who goes against him must be pushing back against the will of the majority and incurring massive social costs... right?

Seems to me it would be very hard for 3 to be true.

First, whenever P doesn't entail Q, P&Q is less probable than P (except in infinitary cases where they both already have probability 0).

So by adding on weird addenda to your view, you're necessarily making it less probable.

Can its probability be decreasing very slowly, while its weirdness is increasing quickly? I don't see why we should think that's in general possible; why should there always be highly weird but not highly improbable propositions consistent with (but not entailed) by any arbitrary weird view you happen to hold? Shouldn't there generally be some connection between weirdness and improbability? (after all, intuition doesn't come from nowhere--it's shaped by cultural and evolutionary learning to be reasonably useful; most things that are counterintuitive are false.)